UNICORNS: THE END OF THE MOMENTUM?

"It's not difficult to create Unicorns, but it's difficult to build a Unicorn that makes money. You can't just say this is indicative of a great market opportunity. It's also indicative of the fact that the founders have not figured out how to make money," K. Vaitheeswaran (the father of Indian e-commerce)

Introduction: what defines a Unicorn

1. Brief History

The first de facto unicorns go back to the late 90s with companies like Akamai, or Webvan. By 2013, using publicly available data from CrunchBase, LinkedIn and Wikipedia, A. Lee found 39 US companies, under 10 years old, that matched the criteria she had adopted to define highly capitalized startups. Since the middle of the last decade, what used to be a rare occurrence in mythology has become almost common.

Life as a unicorn is ephemerous. They are meant either to become publicly listed on an exchange, acquired by or merged with another business, or to disappear by shear failure, and become unicorpses (a term also coined by Aileen Lee). Their lifecycle is no different than any startup. What is different is the process to build a unicorn and of course the scale it reaches in a relatively short time.

2. The Genesis of a Unicorn

First and foremost, a unicorn is designed from day one to address a new market, preferably with network effect. Unlike the larger population of startups that have been used to address clearly identified problems, unicorns frame the problem themselves, not only build a solution to address this extracted problem they have conceived, but, much harder, they thrive in transforming the way potential customers think. In their book “Play Bigger”, A. Ramadan, D. Peterson, C. Lochhead and K. Maney emphasize the importance to design what they call a category within a space, and how a unicorn strategy is to become “the category king”, as competitors eager to penetrate this new category constantly lag behind. “Once a king emerges, customers believe it’s the best, regardless of any evidence to the contrary”, they write.

Success is predicated upon speed. The whole company is preparing for a “lightning strike”, a term coined by the Play Bigger team, when all departments at once launch the major event that will crown the company as the king in its category. “The company’s value is determined by its category’s potential, the company’s position in the category, and its ability to prove it can deliver on its promises.”

This is way beyond the “bull’s eye marketing” approach internet companies have excelled at. It involves the whole company in a thorough and precise planning.

The strength of the barrier to entry is defined as a combination of branding (perception) and execution. It does not exempt unicorns from abiding to conventional business rules to remain successful in the long range. Foundry Group Partner Brad Feld’s four-year-old article illustrated the point, essentially that the moat is much more than a great execution and a savvy branding helped by massive funding.

3. The Shift from B2B to B2C

In the original group that A. Lee characterized in 2013, 15 out of the 39 unicorns were B2B and 24 were B2C companies. Today the ratio has stretched to a 15-85 distribution in favor of consumer-related businesses, except for India where B2B unicorns, all software-related, represent more than 40% of all Indian unicorns.

It is not surprising as businesses with short development turnaround and short sales cycles fit the model. They can alter the landscape and make obsolete a whole industry in a matter of months, provided capital is funding the lightning strike. Such businesses are generally addressing consumers rather than enterprises.

Yet enterprise-oriented unicorns become worth more on average and raise much less private capital than consumer-oriented unicorns, delivering a higher return on private investment. This fact may trigger an inversion of the trend in this decade.

4. Investors’ Appetite and Rationale

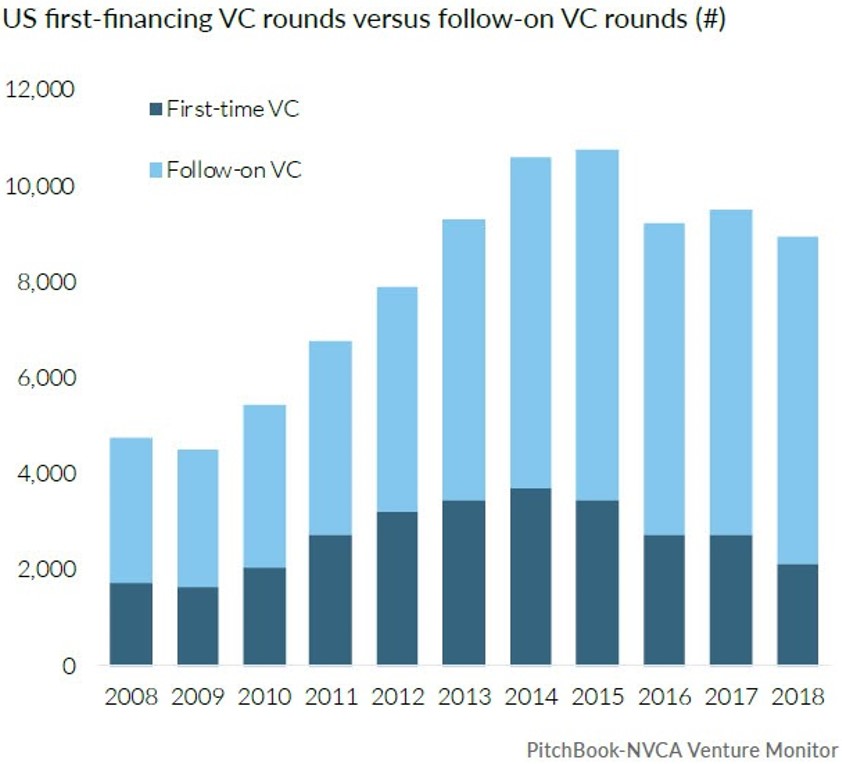

The original aspect of unicorns that struck A. Lee was that all these highly valued companies were not seeking an IPO, at least not as quickly as venture capital-funded companies had done in previous decades. They were rather adding private money after private money, piling up VC rounds. F and G rounds, that in the past were a sign of a lack of visible exit for investors, suddenly came into fashion.

The official rhetoric behind extending private funding in the long range for the deemed giants of tomorrow’s economy is to allow them to remain independent from the big tech companies, i.e. the richest organizations in the world, that, allegedly, would bid for them, in order to protect their turf by putting a lid on the acquired innovation. In other words, private investors inflate the unicorn with big bags of cash so that they become un-acquirable, leaving them (private investors) with one single exit option, an IPO, i.e. a late IPO. Who else indeed could be offered the opportunity to finally invest in a unicorn but institutional investors and the public? IPO investors however are used to a different set of metrics, namely profitability or a clear path to profitability and visibility for years of high growth ahead. What kind of additional value could investors believe these unicorns are going to provide from their IPO price? With a few exceptions-Zoom Video Communications comes to mind- the potential future value is non-existent or at best extremely remote. As a matter of fact, some unicorns agree to be acquired by Big Tech. For instance, GitHub was acquired in 2018 by Microsoft, a company you may have heard of, who also bought Skype, LinkedIn, Yammer, all unicorns.

5. Value and Valuation Should Not Be Confused

In the absence of “bad news”, a unicorn valuation keeps gyrating up to levels unheard of for VC funding of (most often) unprofitable ventures. According to Liam Donohue, from 406 Ventures, “High valuations create perceived momentum; it can make it harder for competitors to raise capital” (quoted in The Boston Globe from 10-6-2019). From 2012 to the mid-2019 in a seller’s market unicorns have taken advantage of a wide pool of available private capital. Uber’s massive funding, $7.3 bn in Series G in 2015, for instance, proved the point. It dwarfed its competitor Lyft’s Series F, “only” $1 bn, which occurred at the same time, a massive funding by any entrepreneur’s standard bar one. Unicorns raised more in late-stage venture rounds than what many companies raised in their IPOs.

If we read this well, private investors leading large funds have changed tack and focus essentially on revenue growth as the guiding metrics, instead of stepping financing stages according to accomplished milestones. The theory of the firm, claiming that, once a firm holds a quasi-monopolistic stake in a market, it controls its price, therefore can rake in fat profits, has not held true for many B2C unicorns. The main reason is that to get customers traction the startup is using a weak business model, based on low price as a weapon to acquire a market. At one later stage, the scale of the business suddenly mandates changes, and the pricing for the product or service must be raised to generate an ongoing profit. The demand then takes a hit, as the loyalty to the brand is not as anchored as suspected. Inevitably, the business valuation, based on the premise of long-term high growth, reverses its course. It is the usual paradox of investment.

6. The Hijacking of Venture Capital

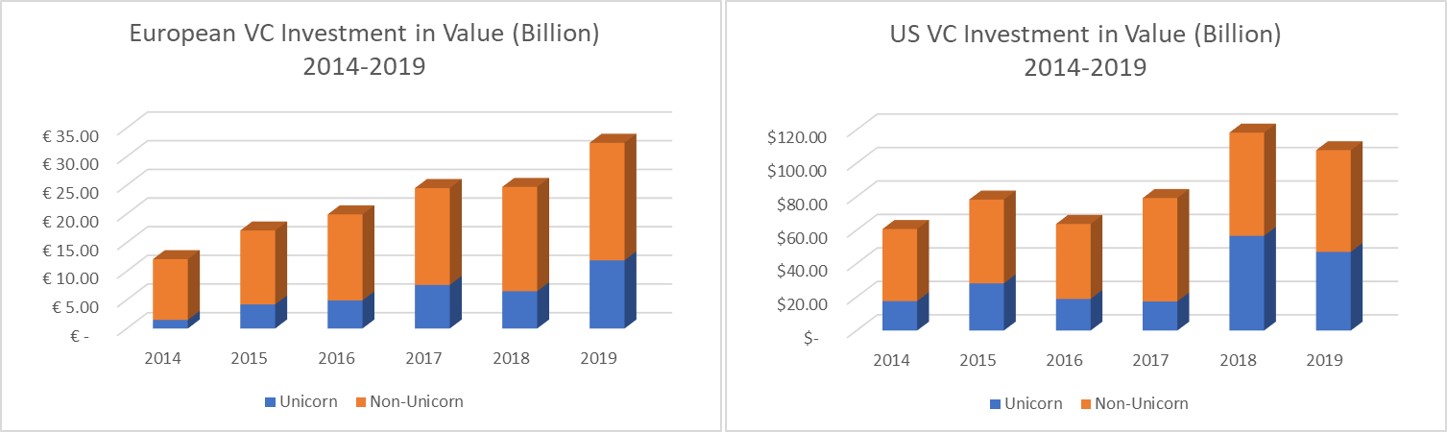

Unicorns worldwide have raised privately more than $390 billion in the last decade, out of total worldwide venture capital funding of $1,192 billion, taking a significant share of the pool of venture capital invested. In the recent period from 2014 to 2019, according to Crunchbase, a total of €36.6 billion were invested in European unicorns, $185.7 billion in the US and $146.7 billion in Asia. The graphs below illustrate the importance taken by unicorn investing.

7. Are Unicorns the Ultimate Model for Tech Entrepreneurs?

It is hard to argue against the success of companies like SpaceX, Zoom Video or Graphcore. B2B deeptech entrepreneurs who are envisaging the launch of a new unicorn, by creating a new category and establishing their ventures as the category leader must expect:

- To forego frugal habits.

- To hire fast and furiously to cover the category territory in a lightning strike, disregarding casualties in the process.

- To never stop communicating in order to impress upon any audience how they are going to own the market they create.

- To keep building a worldwide presence while consolidating the structure in anticipation of becoming a giant.

These are not common traits found in entrepreneurs of deeptech startups. For most of them, I would advise to not be obsessed by the rare extraordinary successes, almost impossible to emulate, and by the numbers that circulate among certain media referring to sky-rocketing unicorn valuations. The bait is not meant for any fish.

Conclusion: Unicorns in Perspective, are they Here to Stay?

I do not have a crystal ball; hence I will not volunteer a shot-from-the-hip response. The deployment of a broad population of unicorns depends upon the international economic situation, the quality and size of the new market categories being created, the availability of piles of cash dedicated to fund the growth of the category leaders, and, last, the average realized returns from investments in past unicorns that exited either through an acquisition or through an IPO. Obviously these four factors are interdependent. The record so far is enticing for M&A events, unlike for IPO events. However, the sample is not yet large enough to provide meaningful averages.

We must acknowledge that the golden period unicorns experienced in the previous decade has been closely linked to the longest economic expansion in the US history and the longest related bull market. The reversal observed in late February/early March 2020, due to the dire world health crisis, will have an impact on the funding of new unicorns, the likelihood of an exit for existing unicorns, and the mortality rate of existing unicorns whose lack of performance will make any subsequent round of financing impossible. Chances are we shall remember the emergence and proliferation of unicorns as another irrational exuberance. Startups involved in capital-intensive industries will keep raising big private rounds. Unlike unicorns, these businesses will be well advised to shun the lightning strike process and its tied “take-the-world-by-storm” message. Unicorns are bound to morph into a more efficient Equidae. May I suggest the thoroughbred?

I will end this blog with a statement a partner from Sequoia Capital made when finally, in 2017 after 9 years of existence, Evernote became cash flow positive: "It's great when a company starts to raise non-dilutive capital every day, which is called revenue.”