THE TRADEOFF BETWEEN GROWTH AND PROFITABILITY

1. Startups are a Vector for Growth

Startups are founded to launch products and services that meet either unexpressed needs or needs somewhat satisfied with poor solutions. They gather resources to take rapidly a significant share of the market, or to create a completely new market. As competitors rarely sit and watch the demise of their own business, startups have no option but to move as fast as possible to be effective in disrupting the market. Growth is then of the essence for startups. Slow-growth technology businesses that address small stable markets are not proper startups, and therefore do not attract the same category of investors.

In the last forty years, startups have been the engine of economic growth in many countries, providing employment - as a by-product, as a famous venture capitalist from the US once claimed- when most traditional businesses have been reducing their workforce.

2. Fast-Growing Startups in Hard Tech Require Significant Funding Upfront

DeepTech startups and other hard tech ones are more capital intensive in their pre-product completion stage than other startups, bar life science ones. They rely upon the availability of significant capital to execute their initial phase.

3. Startup Investors Seek High Returns

Investors in startups, from seed investors to late-stage investors, whether they are private individual investors or institutions such as family offices, venture capital funds or hedge funds, seek higher returns than the ones resulting from an investment in a stock market index, a portfolio of bonds or real estate. They trust the higher risk taken by investing in emerging technology companies is worth a premium in reward. Though the performance of such investment has not shown consistency year after year since the 1970s, it is true that overall, in the long range, the performance has been better, at least for funds with a large portfolio of startups and a professional team of investors. To warrant high returns, investors dismiss any business that addresses a slow-growth market.

Venture capital funds worldwide recorded the best performance among all private capital strategies in the first quarter of 2021, according to PitchBook's latest Benchmarks, with an average internal rate of return (IRR) of 19.8%. On a 15-year horizon, as of 2021 Q1 venture capital had returned in average 11.8% per year (Pitchbook data). The most performant funds extracted IRR above 25%. For the same period, however, an investment in public securities, the NASDAQ Index, returned 13%. This is the reason why institutions and wealthy individuals who invest in venture capital funds, as limited partners, analyze and scrutinize the performance of the fund to broadly outperform the public market. It is also the reason for the small proportion of funds with a long history among all VC firms.

To accomplish these high returns, successful venture capital funds expect to participate in one or two major stars that average up the total return from their investment portfolio. “The correlation between mean realized industry returns and the percent of invested dollars realizing a 10X+ return is .98. This implies that VC industry mean returns are highly impacted by the largest returning financings, in effect that returns are “hits driven”. (David Coats, Correlation Ventures, September 2019). Some funds are lucky once. The great funds have an unparalleled expertise gathered by their general partners and can repeat outstanding performance decade after decade.

4. Opportunities to Invest in Startups have Abounded

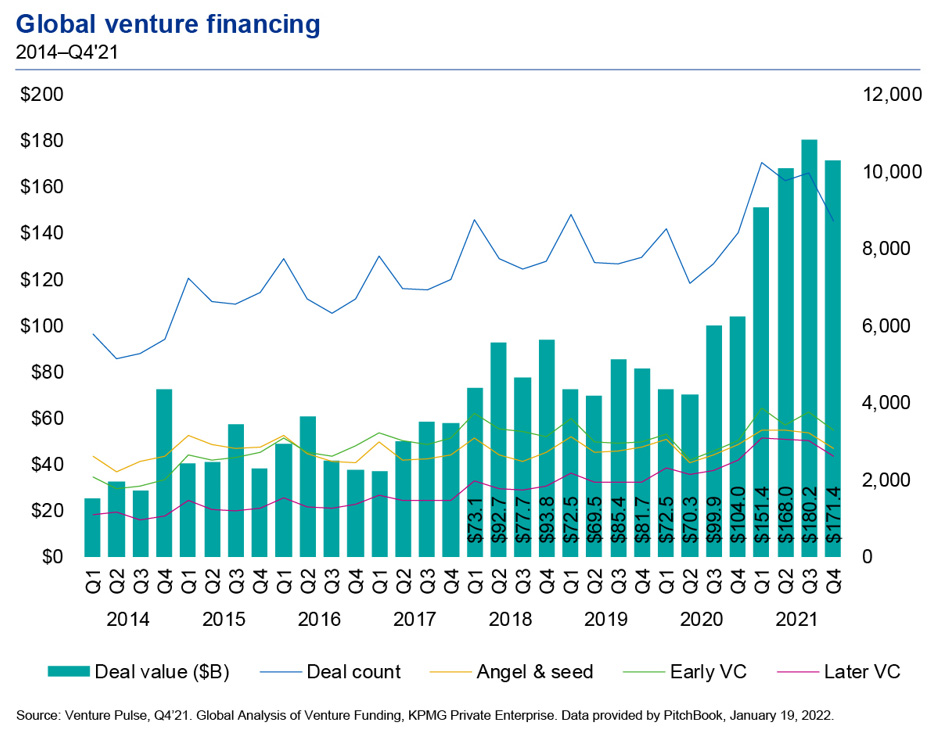

Below is a global view of venture capital funding in the last eight years. The number of deals increased by about 40%, with a higher growth for late-stage deals, while the amount invested multiplied by 6.

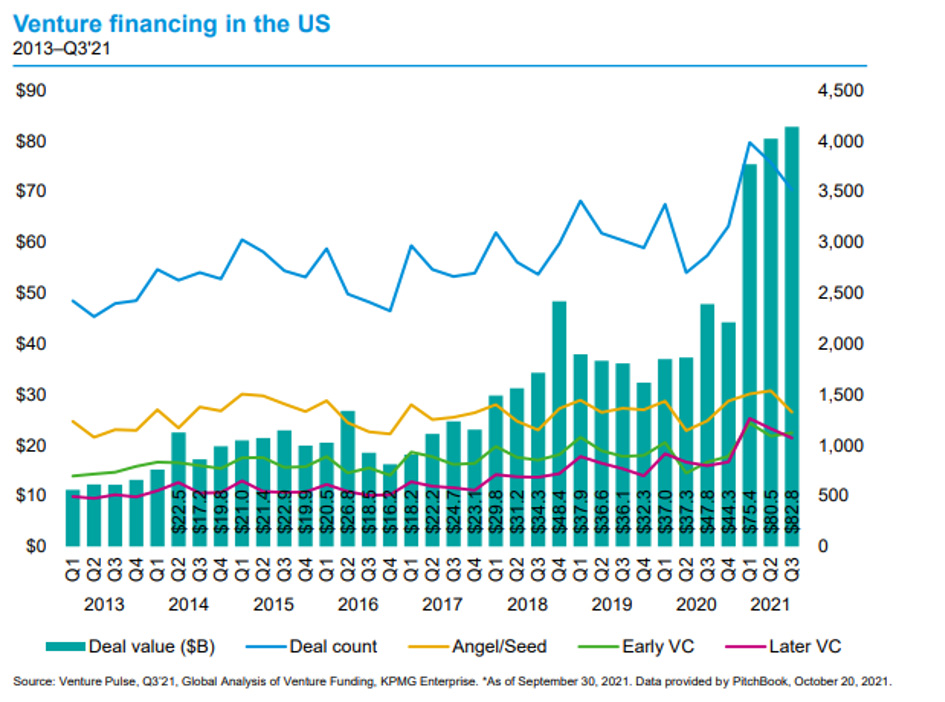

In the US, where venture capital is a mature industry, the trend has been less spectacular, but still exceptional, reminiscent of the late 1990s.

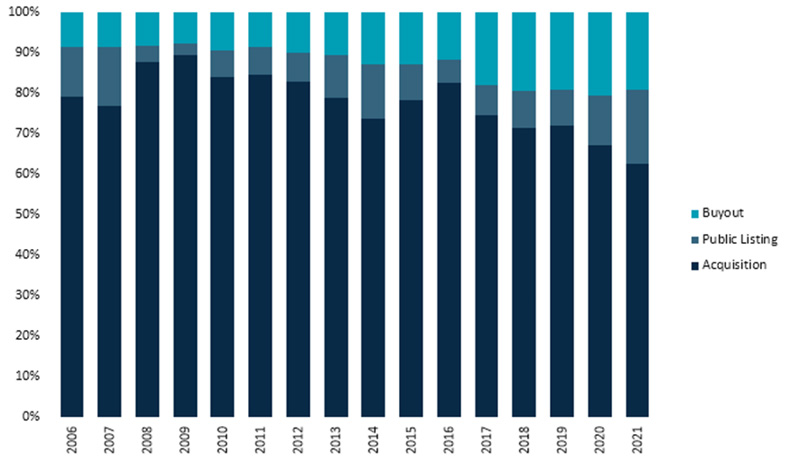

5. Alternate Exits for Investors Seeking High Returns

Investors, before they invest in a startup, share with founders and management their goal as to maximizing their exit. Founders and management may not agree on the timing nor on the type of exit, but they agree on the principle, otherwise their operation must better be able to self-finance its growth. IPOs and mergers and acquisitions (M&As) -including wrap arounds- are the alternate exits. To these traditional exits, we can add the sale to another type of institutional investor, essentially private equity firms who have recently shown an appetite for technology companies in their expansion stage. They started to participate in late-stage private financing alongside venture capital funds, hedge funds and other investors new to this class of investment. Now, some private equity funds are buying majority stakes in late-stage startups. So far, they have concentrated their interest in the software industry where the pool of available management talent is broad.

Last, buyouts come into consideration when the venture does not qualify for an IPO and when no corporate buyer shows interest, yielding returns that are not as high as IPOs or M&As.

Below is the distribution of VC-backed investment exits by number of deals, that shows the importance of mergers and acquisitions in volume.

Source: Pitchbook NVCA Venture Monitor, Q4 2021. January 2022

The same distribution, for the last 11 years, by value shows the bigger size of IPOs vs. acquisitions:

Source: Pitchbook NVCA Venture Monitor, Q4 2021. January 2022

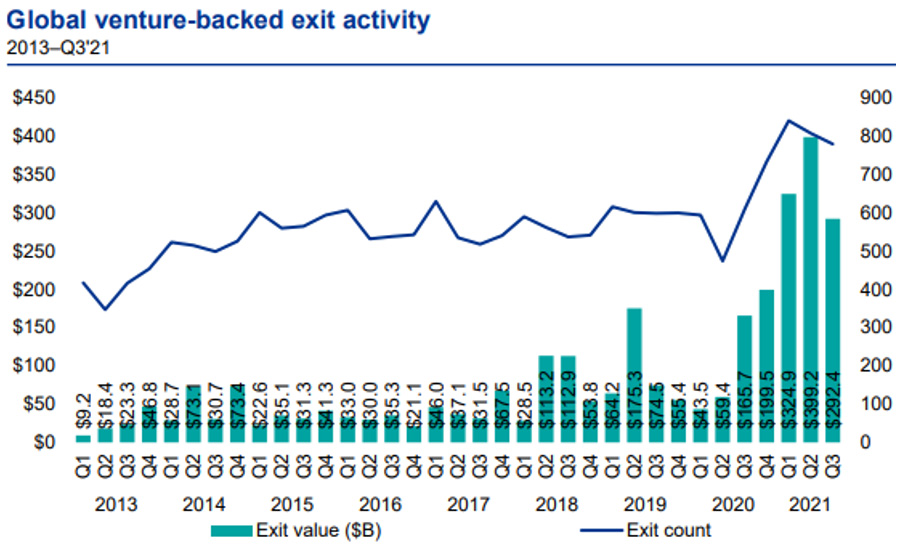

Following the internet bubble, startups have been taking longer in average to file for an IPO. Because of the vast amount of capital available, late-stage rounds have multiplied, while the acceleration of the formation of unicorns with huge private funding have become familiar. Excluding SPACs, that are more of a hybrid instrument, an exceptional number of IPOs worldwide were launched from 2020 Q3 through the end of 2021, freeing a huge amount of capital for VC funds limited partners. Below is a graph showing quarterly data for all exits, including M&As and buyouts for the last nine years.

Source: Venture Pulse, Q3'21. Global Analysis of Venture Funding, KPMG Enterprise. *As of September 30, 2021. Data provided by Pitchbook, October 20, 2021.

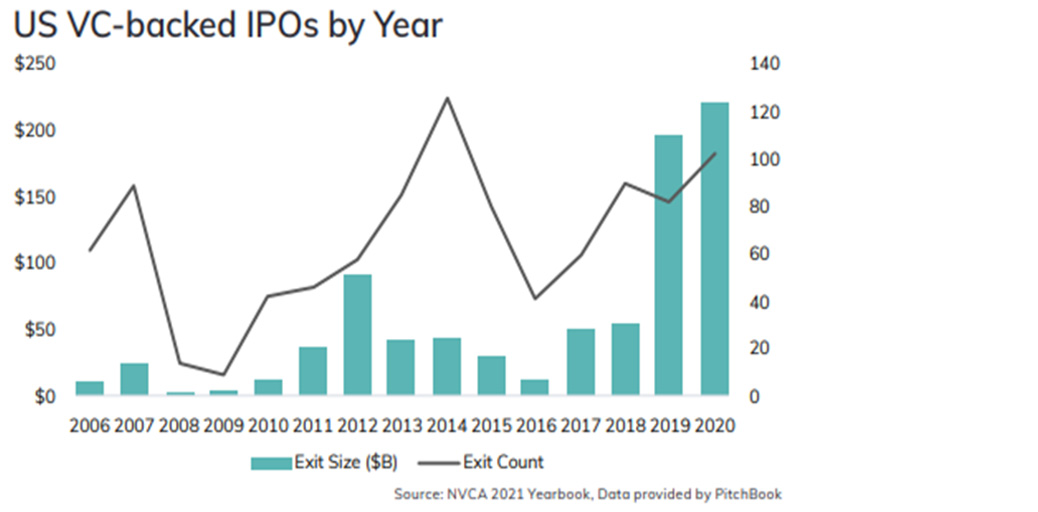

The data for IPOs only for VC-backed investments in the US, below, show a high amount in value in 2012, due to Facebook’s IPO in 2012 and a high number of IPOs in 2014, mainly a reflection of a flurry of life science companies taking advantage of an improving market. The same year, for the first time in 7 years the median amount raised by IPOs was lower. This is the more remarkable as it was the year of the massive Ali Baba IPO for $21.8 billion.

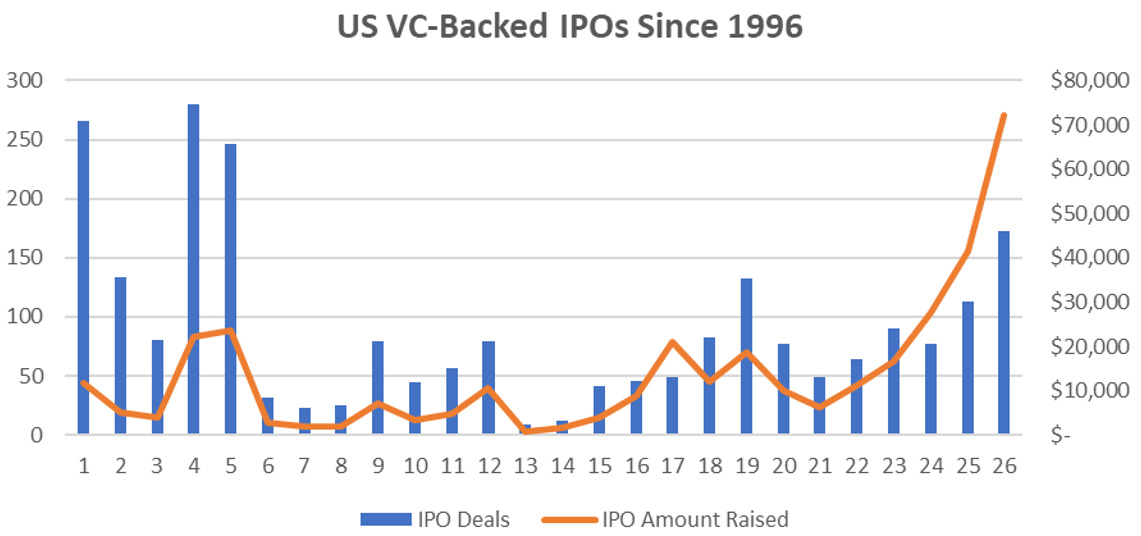

For a longer period, starting in the mid-1990s until the end of 2021 (years 1 to 26 below), it is striking that there were more IPOs during the dot.com period than in the last three years, while the value of the IPOs was significantly lower then. There was 1006 VC-backed IPOs between 1996 and 2000 that raised cumulatively $66.6 billion, whereas between 2017 and 2021, there was 516 VC-backed IPOs (about half the number of twenty years before) that raised $169.2 billion, two and a half times the amount raised twenty years before. In constant dollar it would still represent an increase of 58% over the previous golden age.

Source: Jay Ritter, Warrington College of Business, January 2022

6. The Importance of the Stock Market Behavior

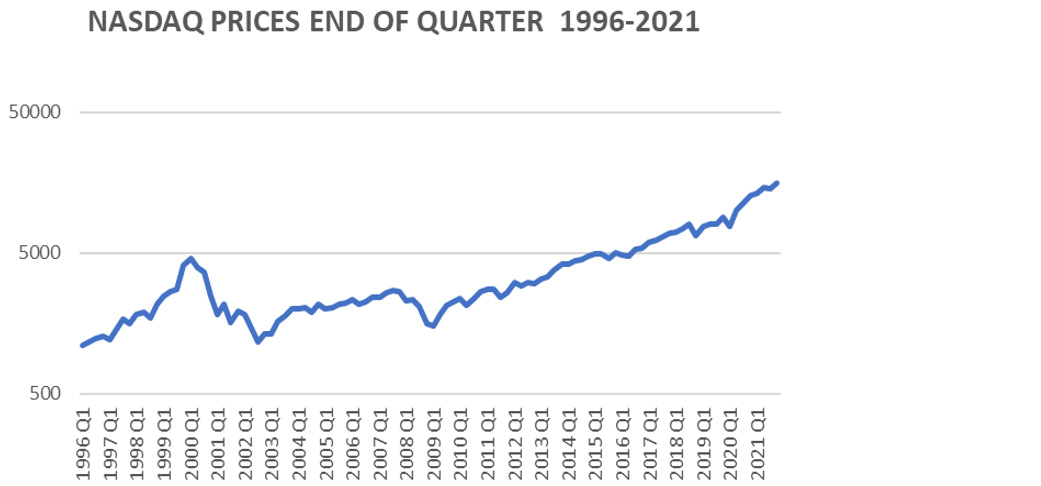

Memories of the rapid slide of NASDAQ index in 2000, falling from a peak of 5027 on March 10, 2000, to 2470 at the end of the year 2000, all the way down to 1114 on October 9, 2002, have not been erased through the longest bull cycle in history we have just experience following the great recession of 2008.

Source: Yahoo Finance

The stock market plays a crucial role in the economy, first obviously because it funds successful businesses that can envisage a further expansion, and, second, because it releases capital, at IPOs, to fuel again future startups and start the cycle again. This cyclicality feeds itself: when the stock market reaches records, VC raise funding for their funds as they have exited a large number of investments, returned money to their limited partners and then turn and ask them again for money to feed new funds, ready to invest in the new generation of technologies. This cycle, however, is not totally smooth. Some periods with static or receding stock market may last long and money available for financing investments at VCs tend to dry, as limited partners are reluctant to participate in VC fund raising considering their less than stellar performance. Only big names with a long outstanding record can still raise funds in those times.

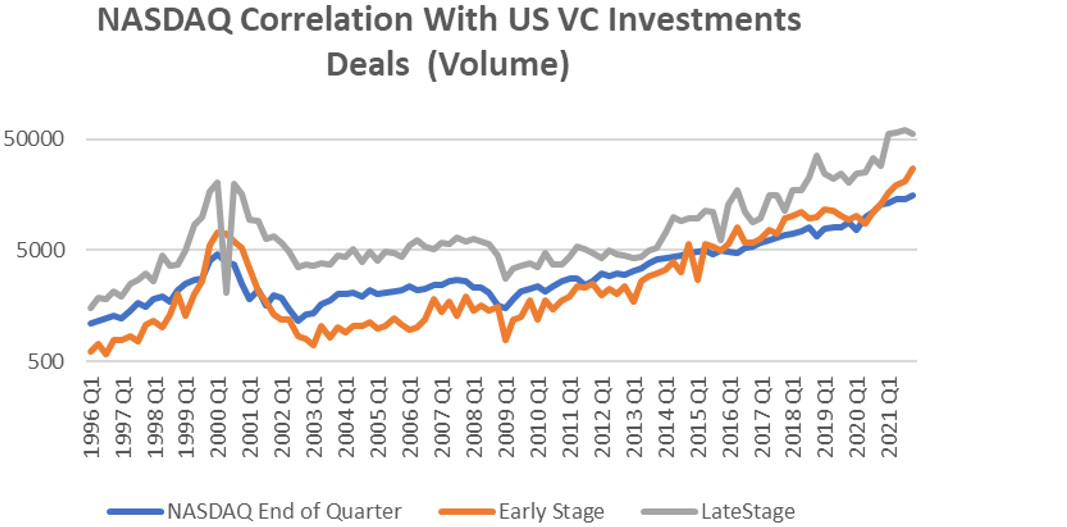

a. Is there a correlation between the stock markets and VC funding?

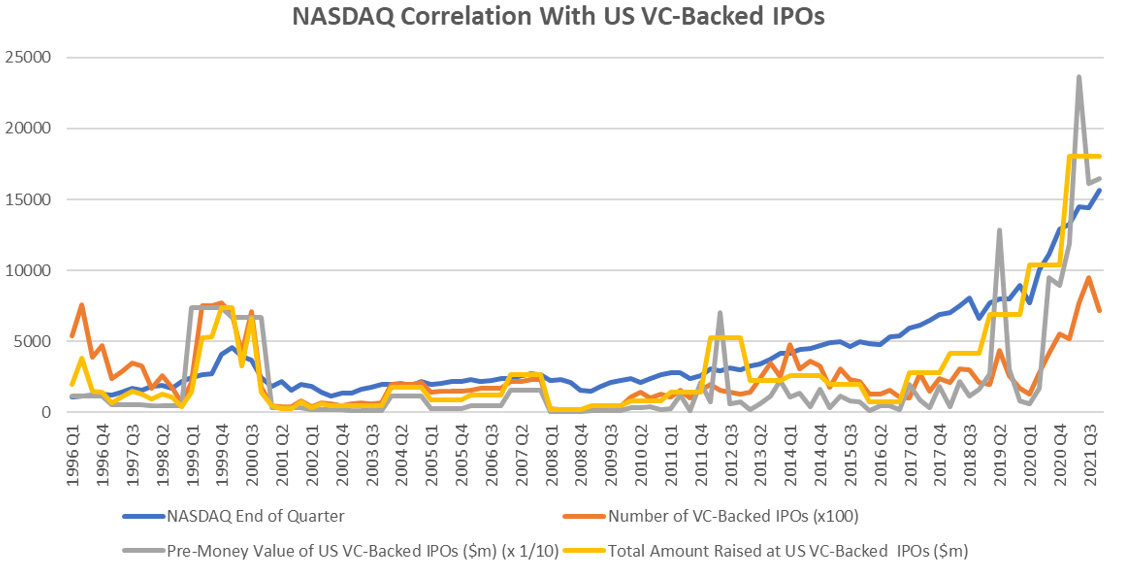

The intuitive correlation between the prime stock index for technologies, NASDAQ, and the number of VC deals in the US is confirmed for the period 1996-2021. In other words, a high stock market gives confidence to venture capital firms to invest in new ventures.

Source: Data from NVCA/Pitchbook , Dow Jones VentureSource, Opalesque.

The correlation coefficient for late-stage deals with NASDAQ is a moderate 0.663. However, if we consider a 3-month delay, the correlation coefficient reaches a more significant value of 0.937. The correlation for early-stage deals, with a 3-months lag is higher, at 0.967. Hence, we can infer that the funding for new startups may be affected if a serious correction occurs in the value of NASDAQ. A quick look at the graph shows higher amplitude swings for VC deals than for the stock market.

b. Is there a correlation between the stock market and IPOs?

It has been generally considered that a drought of IPOs affect more the price at which VC invest in companies than the willingness to invest, i.e. the number of investments. From an early-stage investment to an IPO, the road takes years (5 years in average in the late 1990s, 8 years for recent IPOs).

This graph shows a low correlation of 0.494 between the number of VC-backed IPOs and the NASDAQ Index. Even taking a 3-month delay into consideration, the coefficient is remarkably stable at 0.497. Using a 6-months lag the coefficient is 0.509. This is due to the lack of easily available data for the first years. I opted for an equal distribution per quarter of yearly data until 2009 reducing the impact of inflexion points. There is no doubt that the real correlation was higher. For the period 2010-2021 the correlation is higher, at 0.81 with a 3-month lag. The correlation between the amount raised in IPOs and NASDAQ is approximately the same at 0.79.

7. The Role of Secondaries as a Palliative

When market conditions are unfavorable to listing new VC-backed companies, and when simultaneously potential corporate buyers become rare, venture capital funds as well as partners and executives in such companies may turn to secondaries that buy -at a discount from the last financing round- shares of existing private companies. As institutions specializing in secondaries are not restricted with an horizon akin to those of VC funds, they can exert patience. It goes without saying that institutions buying secondaries do a thorough due diligence and not all VC-backed companies pass the test. Their goal is obviously to realize a high IRR. The risk they take is linked to the capacity of the venture to remain afloat and improve its operating cashflow during “dry times”. The first secondaries came out when the IPO market was almost inexistant in the period 2001-2003. They fill a need for liquidity felt by investors, founders and management in certain cases.

Since secondary offers of unprofitable VC-backed companies have been in existence, there is less reluctance to push growth to its maximum possible, whatever the consequence is for the balance sheet.

8. Is the Pendulum turning in favor of startups with positive cashflow?

Entrepreneurs must seek ways to enhance growth while accelerating the time to profitability. Tech startups are founded to offer technology and products that, by their uniqueness, allow to carve a niche. It is essential that they quickly extend the niche into a sizable market. This will likely occur at the expense of profitability, through external funding. Investors, especially VCs and Private Equity (PE) seek to accelerate growth to own a market. In the last decade investors have favored growth over profits. Unprofitable high-profile unicorns with $1 billion annual burn rate became possible. Only a long bull market could provide an exit to their investors, more particularly to their last round investors.

Founders with a view to build a long-lasting business with successive vision phases seek to secure the assets thus built, mitigating risks as much as possible. In times of capital drought, fast growth becomes secondary to profitability in their survival kit. The generation of positive cash flow is the priority. “Being profitable certainly makes your company more sustainable in difficult times.” (Mark Suster)

If the IPO road narrows a lot or even closes like it did in 2008-2013, startups need to work hard at improving their operating cashflow as they must preserve cash, unless they are ready for a new private round of financing, more likely severely diluting their stake, a “down round” in other words.

What about the road to M&A exit, would you retort?

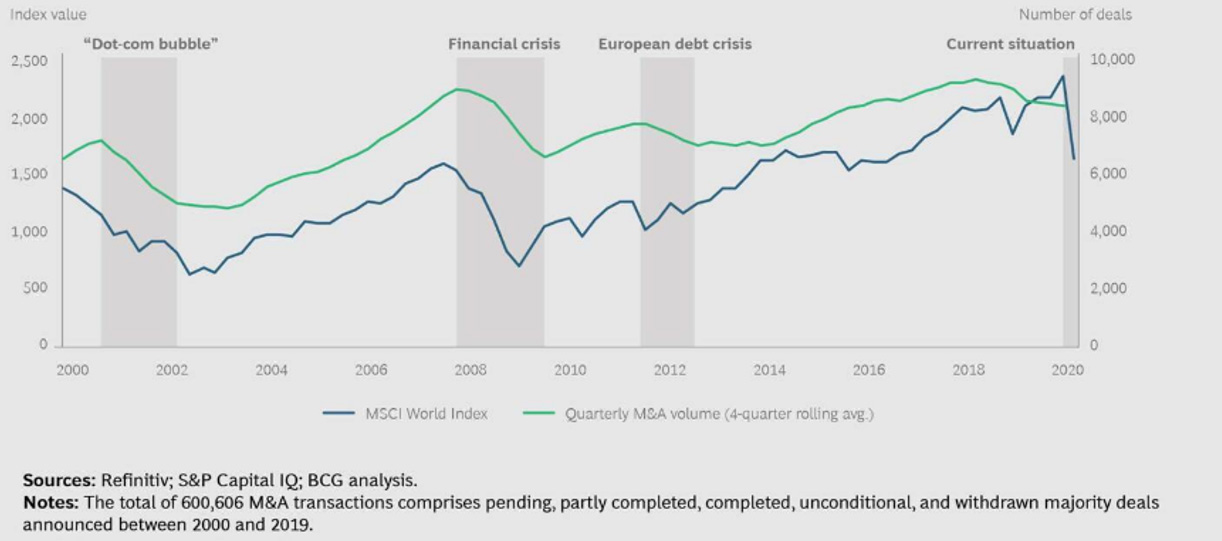

“Historically, M&A activity has correlated strongly with the evolution of stock prices and risk, as measured by implied volatility. From 2000 through 2019, the correlation between the value of the MSCI World index and M&A volume was approximately 80%.“ (BCG, March 20, 2020)

“For companies that have built a healthy balance sheet during the economic boom of the past ten years, declining valuations create opportunities to pursue deals that create long-term value.” (BCG)

Conclusion

DeepTech entrepreneurs need not fall into panic mode about the high volatility of technology stocks. It does not mirror what will happen soon to startup financings. Most venture capital firms are cash rich today. They are not going to deviate from their practice, except that they will, legitimately, seek to be more demanding for the price of their investment. It is doubtful the number of investments by VC will be significantly affected within the next six months. If new alarming events surface, it would then be likely that VC firms become more cautious in their approach. DeepTech, as Life Science, are much less volatile than other industries. As a rule, entrepreneurs must keep opening new markets and accelerate their penetration. Good planning avoids many costly pitfalls. Throwing money at an issue is never a path to success. On the other hand, putting the brakes on all four and staying put to conserve cash at any rate may cost you a dominant position in an emerging market. Iconic companies were started in times of downturn.