THE MORPHING OF VENTURE CAPITAL

How did this happen, and are traditional venture capital firm equipped to fight back and regain the total ownership of startup investing? Do Entrepreneurs benefit from this competition?

1. The Trend Toward Bigger Financing Rounds

Since the beginning of the last decade, technology startups funding rounds have become ever greater. It began when competition to invest into the next huge thing became intense. Entrepreneurs in these expected big successes have played their hands to what looked like, on the surface, their advantage.

a. Late-Stage Rounds Soared

Globally the amount invested in rounds of at least $100 million represented about 50% of all funding to startups by 2017 and 65% by 2021. In 2021, more than ten rounds of at least $1 billion closed. As Bill Gurley was pointing out as early as February 2015, “late-stage investors, desperately afraid of missing out on acquiring shareholding positions in possible “unicorn” companies, have essentially abandoned their traditional risk analysis.” Together with the increase of late stage deals median size triggered by the growing importance of mega deals, the valuation of late-stage deals tripled from 2017 to 2020 (Pitchbook, March 2022).

b. It Trickled Down to Early-Stage Rounds

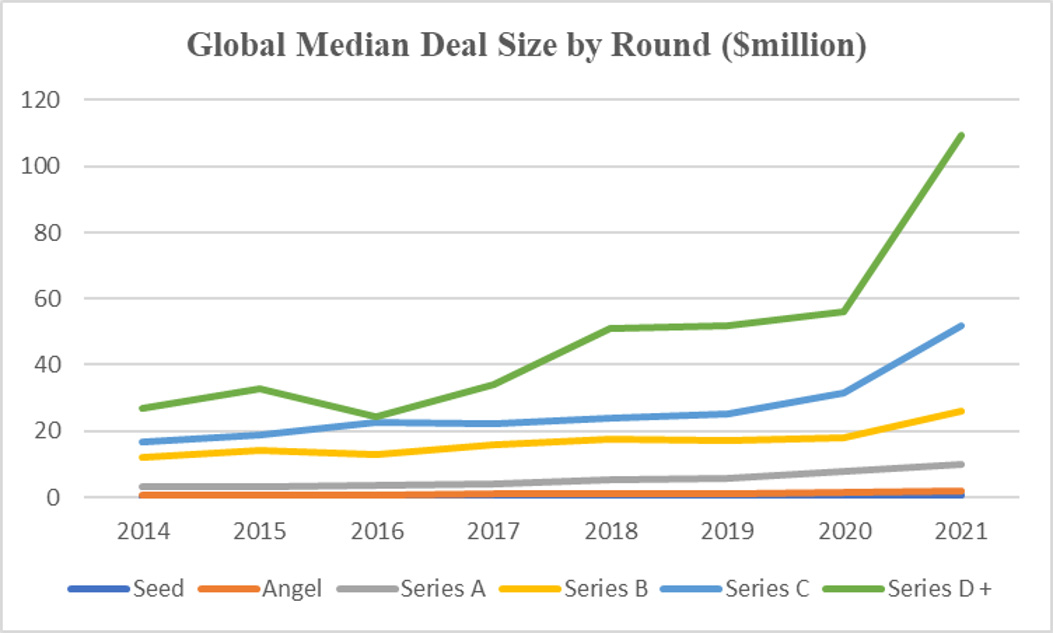

Until 2019, only Series D median size had doubled from 2014, i. e. in 5 years. Series C in 2019, then Series B in 2020 and even Series A in 2021 grew in median size at a faster rate than in the past. Below is the global evolution of median deal size by Series ($ million)

Source: Pitchbook Dtata, January 2022

The inflexion in favor of mega deals appeared in 2017, when a vast cohort of Chinese unicorns were created.

2. The Trend Toward Extending the Private Status of VC-Funded Companies

Since the 2008 financial crisis, late-stage VC-funded startups have successfully managed to raise funds privately in more successive rounds than in past decades. Extreme examples such as SpaceX, founded in 2002 and the recipient of almost $6 billion in equity funding, Klarna, founded in 2005 and funded with more than $3.7 billion, and Stripe, founded in 2009 and the recipient of $2.2 billion so far, come to mind. As the IPO market was atone for years, venture capital funds stepped up to keep funding companies they regarded as winners, though most of these companies were unprofitable for a longer period.

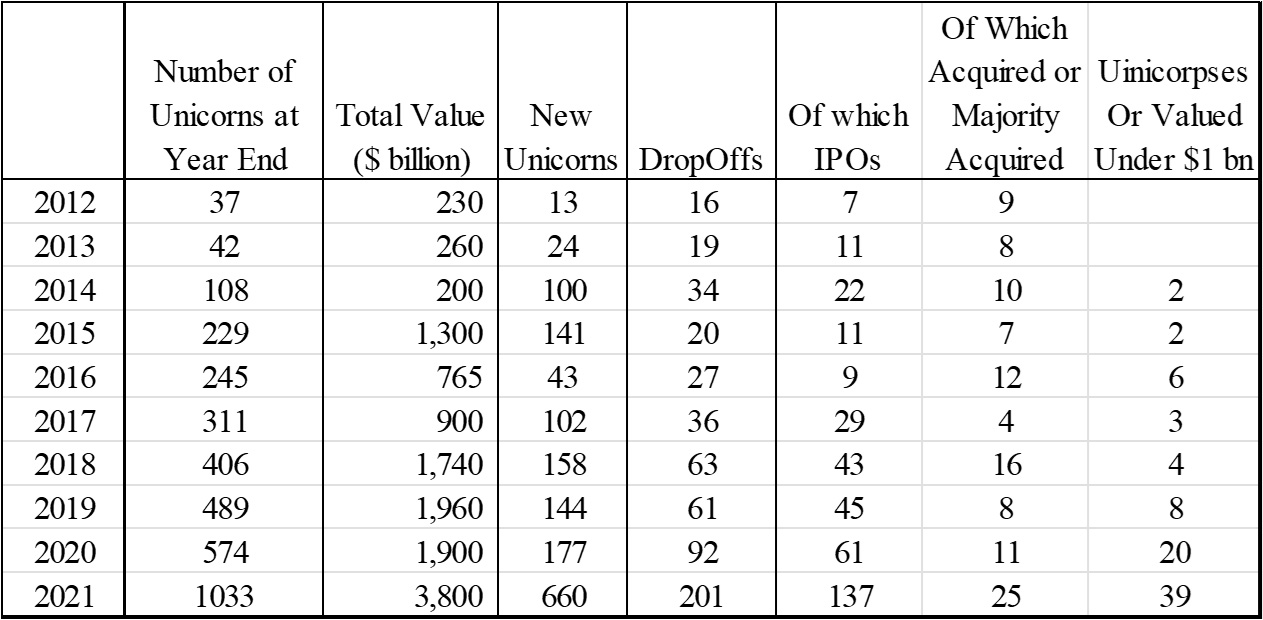

Increased valuations were based upon the assumed ability to grab a dominant market share, regardless of the burn rate. Successful technology companies that used to take 5 years in average from their first institutional round to an IPO would take 7-to-8 years, between 2009 and 2017. With the large rush to IPO in 2020-21, the gap has decreased to about 6 years. In 2021 alone, 137 unicorns had a successful IPO, vs. 61 in 2020.

3. The Focus on Building Unicorns

As a result, large VC firms and growth-stage private equity firms built a growing portfolio of unicorns. The rationale behind such a bold approach to risk investment is the conviction that either a big IPO or an acquisition were inevitable, based on the achievement of these unicorns at the time of their last private funding round. In 2019, $39 billion, in 2020, $52 billion and $138 billion in 2021 were invested in unicorns alone.

Below is an approximate table showing the evolution of the global unicorn community. It was built from data sourced from Bloomberg, CB Insights, Crunchbase, Harvard Law School, Hurun Reports, Pitchbook, PwC Venture, VentureBeat. As all these organizations track unicorns, one would think there would be a consensus on basic data. Not so, as most elect to capture these data at a random date that is not a year end, and each one does not precisely adopt the definition given by Aileen Lee in her seminal article from November 2013, more specifically some comprise private technology companies funded by institutions other than venture capital for example. Hence, the data gathered below have coherence, but I cannot guarantee their accuracy throughout the ten-year period. The trend, by column, is what matters here. Indeed, venture capital firms have funded more unicorns, year after year, and not only in the USA and China, but now in more than thirty other countries.

So far, this evolution has proven me wrong as to my prediction two years ago that the momentum for unicorns was coming to an end. My fundamental views on unicorns have not changed, though.

Funding 660 new unicorns globally in a single year through mega rounds of private financing, almost all above $100 million, demonstrates a significant amount of money is invested in big late-stage rounds. Growth stage funds with different investment practices than VC have rushed to participate in these late rounds and fill a gap that only large VC funds can fill. Hence, these investors with fat checks, no requirement for a board seat and simple term sheets have been welcome by entrepreneurs. These investors anticipate a fast exit, in less than three years. In 2021 some investments were exited in less than a year. Venture capital specialists feel somehow taken advantage of. In crude words, they do all the hard work during the early years of a startup, assisting entrepreneurs build value, and when the startup is well on its way to a big success, huge growth-stage funds join the party and quickly obtain a high return on their money at relatively low risk, defying the old rule of parallel movement between risk and reward. At least that was a repeated scenario in 2021.

4. The Belief That the Outrageous Years 2020 and 2021 Are the New Reference

Many venture capital firms found they were sharing late-stage funding of their portfolio companies without much discrimination. If they could raise large funds themselves, they would participate in large late-stage deals in a bigger way and take home a bigger prize. It is a legitimate reasoning, assuming (i) we are witnessing a long-term pattern in technology startups, with no end to the creation of category-defining unicorns; (ii) unicorns address massive markets; (iii) no disruptor will unseat any unicorn; (iv) bear markets are of short duration. It is a big leap of faith.

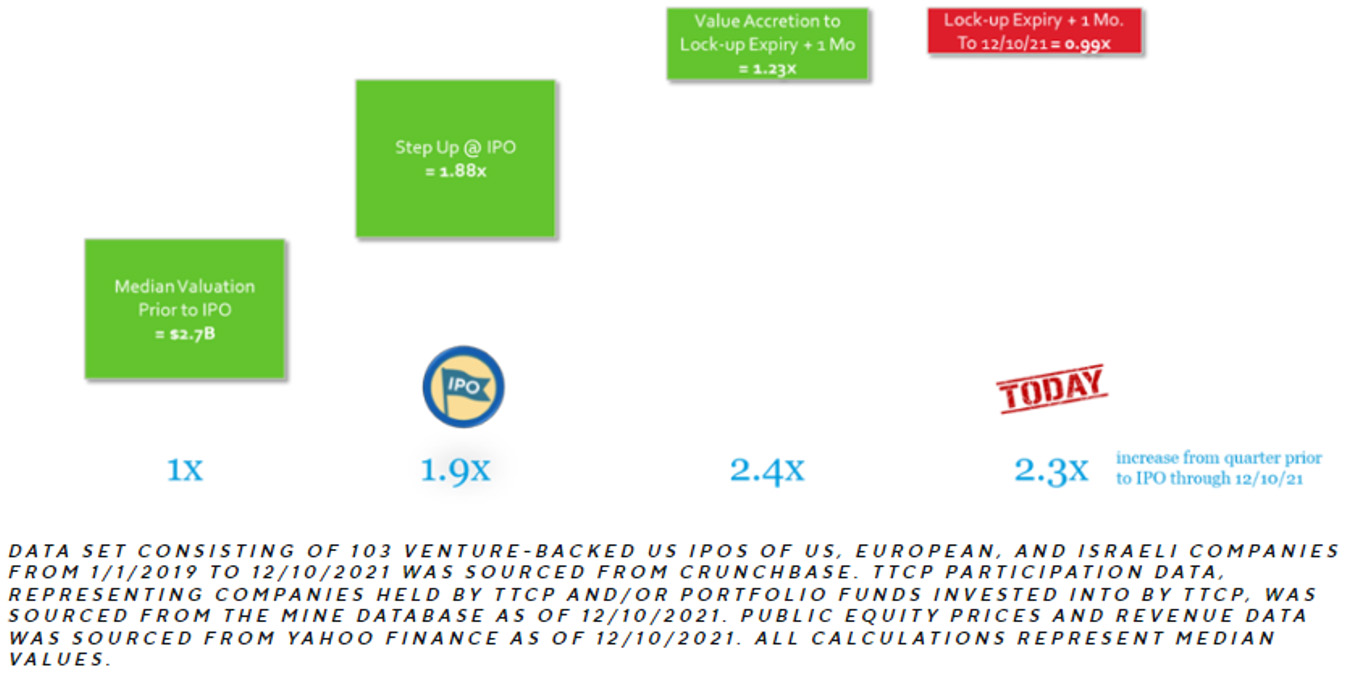

What VCs are leaving on the table has been significant indeed in the recent successful unicorn IPOs. Out of 130 unicorns that had a successful IPO, the average valuation jumped by 60% from the last funding round in about twelve months (source: Crunchbase, October 2020). In the last three years, “venture-backed IPO valuations were 2.3x higher than those of the respective company valuations the quarter prior to IPO.” (Top Tier Capital Partners, December 2021)

Source: Top Tier Capital Partners December 2021

5. IPOs are Still Luring the Most Successful Growth Companies

There is no running around the bush, IPOs are still the best way to realize value at one time of the startup lifecycle. Examples of acquisitions or potential acquisitions (like Facebook’s offers for Snap in 2013 and again in 2016) where prices are extremely high do exist, albeit rarely. In general, whether acquisitions are offensive or defensive, they are executed at a value that makes sense for the acquiror based on a 3-to-5-year analysis, whereas an IPO is sold by investment bankers with a long-term horizon model, and above all according to the appetite of public investors, which appetite was very whetted in the last three years.

Traditionally, in the last 50 + years, the wealth of venture capital and of VC limited partners came from the listing of portfolio companies on a stock exchange. It remains so as of today. The appetite of IPO investors for the listing of high technology startups has been cyclical; periods of enthusiasm that trigger a rush of IPOs are followed by periods of total lack of interest.

If market conditions are not favorable for IPOs, the options for entrepreneurs and investors are either to find an acquirer and sell the company, to fit the VCs funds’ horizon, or wait for market conditions to improve and prepare for an IPO. In the second option, companies with negative cash flow, which is the case of the estimated majority of unicorns, will require additional funding. Only big pocket investors with multiple funds allowing for a longer investment period will meet with the requirements.

6. The Broken Risk-Reward Hierarchy

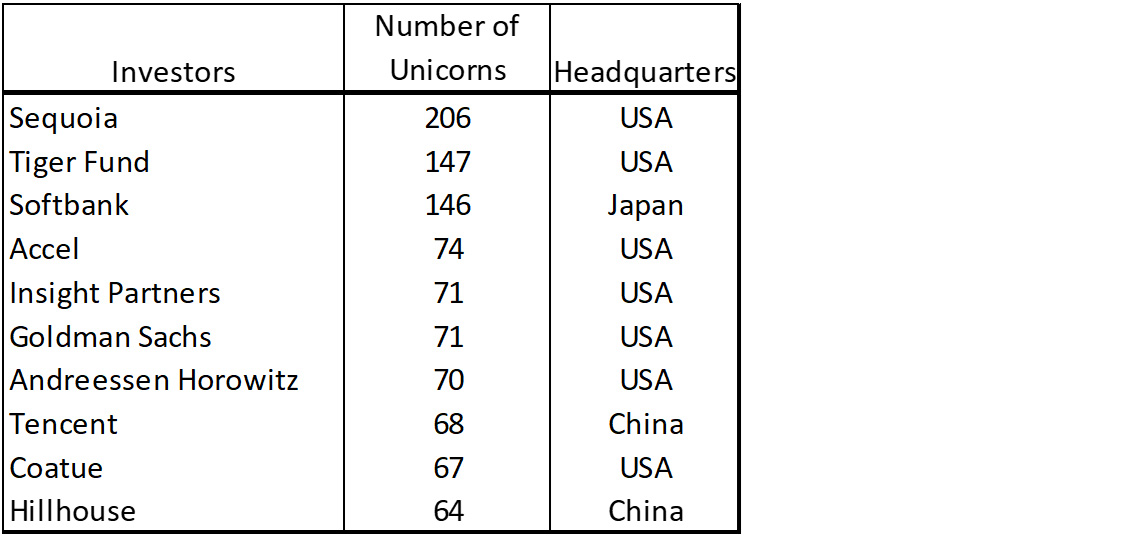

As mentioned above, non-VC investors found high return opportunities in participating in late-stage rounds. Hedge funds and investment funds, flush with capital, with no experience in venture capital, easily accepted high valuations, their sole purpose being to get in at the right time, pre-IPO. They rarely take a board seat in the venture. A recent report from Goldman Sachs found that hedge funds invested an incremental $153 billion into private companies in the first half of this year, compared with $96 billion in all of 2020. Pitchbook estimates that this group of investors is sitting on a cumulative $350 billion worth of investable capital as of October 2021. The following list of the top ten investor in unicorns shows how VCs have relinquished their leading position and let this new group take a sizeable slice of the market of pre-IPO unicorn investing.

source: Hurun Global Unicorn Index 2021

Four out of the top ten unicorn investors are traditional venture capital firms, all based in the US. Otherwise, Softbank is a large Japan-based investment holding whose venture capital activity worldwide is one among many other investment activities. Its founder has generated much controversy in the last twenty years with his untraditional approach to investing in technology startups. Its Vision Funds (1 and 2) are giant investment funds dedicated to investing in future category leaders. Tiger and Coatue are New York-based hedge funds partly turned venture capital firms investing worldwide. It is not clear whether it is an opportunistic move to take advantage of a favorable stock market situation, or a definite long-term strategy. Hong-Kong-based Hillhouse Capital is also a hedge fund turned investor in private technology companies. Goldman Sachs is constantly blurring its activities on behalf of clients and those on behalf of its shareholders. They recently set up a giant growth equity fund for their clients to access mega deals. They have a potential vested interest in the success of these companies as they see them as future clients for their IPO underwriting activity, a very high margin business. Tencent is a conglomerate with a broad portfolio of technology and media investments that they started to build less than ten years ago. Some analysts estimate their portfolio to be valued at more than $250 billion.

Index Ventures, Balderton Capital and Eurazeo are the top three most successful European unicorn investors. The first two are pure venture capital firms.

The hijack of unicorn investing by deep pocket financial groups has disturbed the high-end venture capital firms who had traditionally considered the investment in fast-growing private technology companies as their turf. The opening of a fault has been very prompt, and some VC firms realized they had to alter their model to not be despoiled by the newcomers with little expertise in the class of investment they, VCs, have specialized for decades.

7. The VC’s Parry

Venture capitalists feel threatened in their core business. Today they could claim that they are the ones with the right expertise to invest in technology startups and assist their leaders to grow successfully. It is true, and no one would argue. Yet, nothing prevents the large private investment funds and hedge funds to build a competing core expertise by hiring talent from the large pool of General Partners in stellar VC firms. We shall watch what kind of compensation packages will lure the good VCs to their nemesis. The atmosphere is that of investors who feel they do the hard work, hold their stakes a long time, only to watch a group of newcomers with big coffers ready to plough money in late rounds and reap a bonanza in less than 2 years. It does feel as if the risk-reward relationship has been skewed. Three venture capital firms have responded to the challenge: Sequoia, the grande dame of Silicon Valley and #1 investor in unicorns, Upfront ventures, from Los Angeles, and Munich-based HV Capital so far have announced changes they are making in their model.

Upfront Ventures and HV Capital both set up a “continuation fund”. As its name suggests such fund allows the VC firm to keep supporting companies in their portfolio that will remain private longer.

Sequoia’s answer is the creation of a master open-ended fund, dubbed The Sequoia Fund, holding a liquid portfolio of shares in public companies and not bound by the traditional 10-year locked period typical of the VC industry. The Sequoia Fund will allocate capital to Sequoia closed end funds, present and future, dedicated to all stages of development up to IPO. The rationale is to align the interest of Sequoia with those of the visionary entrepreneurs who stay on board long after the IPO and have a long horizon to execute on their vision. More candid would have been to suggest that Sequoia’s intent was to go where the highest value was being built. In the case of some category leading companies, this occurs after the IPO, though only in the minority of cases.

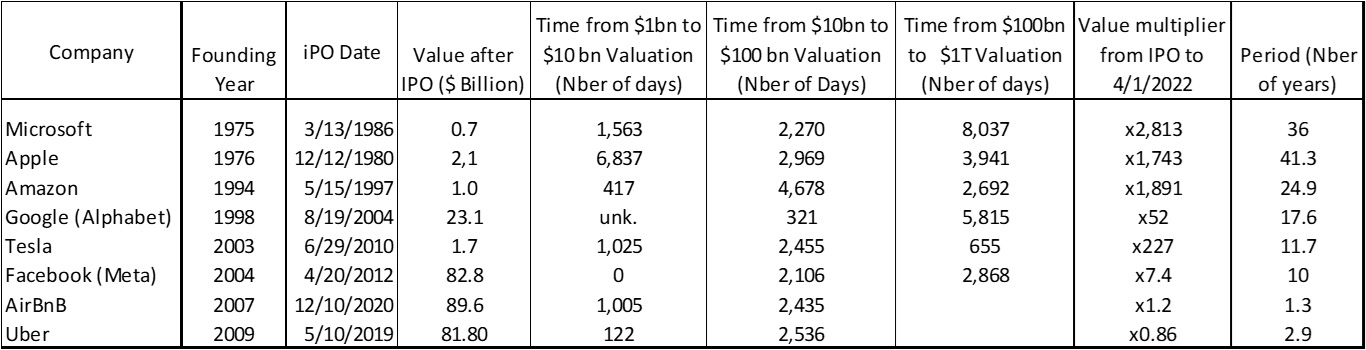

Top-tier unicorns are expected to move to another scale of value within a decade following their IPO. Below is a table describing the performance of today’s tech giants since the days of their IPO in comparison with recently listed unicorns. Tesla is the star example of a great success: the company went public at a post-IPO valuation of $1.7 billion on 6/29/2010, when the stock market had not yet recovered from the 2008 crisis. Ten years later, the company’s value on NASDAQ was $297 billion, which, after considering the secondary financings that diluted initial investors, represented a multiplier of 71.7 on the IPO valuation (post-IPO). This is the kind of multiplier that attracts big VC firms.

Source: Data from Yahoo Finance

If other big VC firms, think Andreessen Horowitz for instance, are keen on emulating the new Sequoia structure, it will be interesting to watch how many upcoming listed unicorns will qualify to remain in their portfolio, past their IPOs. Unlike Tiger Global, who plays as many chips as it can have access to, and has not been a long holder beyond IPOs, Sequoia and its followers will apply their expertise to develop a process that will help them determine when to sell. This will be their biggest challenge.

8. Is This New Development Good for Startup Entrepreneurs and Management?

These moves, so far sporadic, though no doubt to be emulated by other VC firms, raise a flag for early-stage startups that may not have the vision and the pedigree to become a category disruptor candidate in an investor portfolio. The way one can interpret this is that firms that have been picking unicorns with success will keep investing in early-stage startups as in the past. However, they may not participate in the same proportion in Series B (or Series C) from the companies in which they invested in Series A. The bar will be raised higher, and many outstanding startups will not have access to first class VCs from a certain stage, as these VCs will narrow the funnel to identified unicorns and focus on making them successful. Their rationale is clear. They will have the potential to provide higher returns to their limited partners and their general partners.

As the capital market never leaves a vacuum for long, one can be certain that a new generation of investors will broaden their expertise. Among the thousands of early-stage VCs, maybe one hundred will step up and lead Series B, C and beyond, if need be, to warrant the success of companies that may not reach a $1 billion valuation within 3-to-6 years but still provide handsome returns.

Conclusion:

Long-standing, highly successful and respected venture capital firms are attempting to secure their position as the leading group investing in highly valued startups that define new categories. Some will cross the Rubicon and start holding public companies stakes much longer than they used to. They will still remain prime investors in early-stage rounds of startups. That is where their expertise has been praised. Managing a portfolio of publicly traded companies is another expertise, taking into account aspects that are external to the investee ecosystem. Nurturing unicorns at exceptionally high valuation does not imply these same unicorns will keep growing as public companies. For one Tesla, how many will fall flat on their face?

DeepTech and biotech startups need not worry. The select group of investors aiming at accompanying entrepreneurs in these industries will not change the course.