THE ERA OF THE APEX PREDATOR

I. The Concept of Enterprise Life Cycle

a. Origin

Organizations are likened to living organisms. The English economist Alfred Marshall is credited for alluding to the concept of life cycle in businesses, in Principles of Economics (1890), where he compared the growth of young trees in a forest to the growth of business organizations. From the 1950s on academics have developed several models describing organizations life cycle, through a sequence of phases, from birth to extinction. Models were differentiated by the number of phases, anywhere from three to ten, and incidentally by the name given to each phase. As the analogy with a biological being remains central to the model, the sequence in all models is irreversible.

b. Simplified Model

Most commonly a business life cycle is divided into four stages mirroring a biological life: birth, growth, maturity and decline. Each phase is characterized by multiple traits. Though it is over simplifying, as an organization does not suddenly jump from Phase One to Phase Two, etc, it allows observers, but also entrepreneurs and management to situate an organization within the four-phase lifecycle, and use this knowledge to either move to the following phase, or to extend the present phase.

i. Phase One: birth (Startup Phase)

Founders develop a product or a service, build an enticing value proposition and adopt a business model to maximize revenue generation. At that stage the business, most likely, is dependent on outside funding to sustain operations. Cash flow may become positive at the end of the phase. This phase can last a few months up to more than a decade if investments to develop and build the product are important. This is the case for instance for nuclear fusion startups or some biotech companies

ii. Phase Two: Growth

In the growth phase, revenue increases rapidly, incurring positive cash flow and ultimately net profit, bringing financial independence, until new markets are explored.

iii. Phase Three: Maturity

A successful business matures when its market position is maintained, in a market that has stopped growing. Though revenue (in volume) tends to reach a ceiling, the business generates a maximum of cash as investments in R&D had long been completely depreciated. It is the most critical phase, as management must not be complacent but must set a strategy to avoid rolling into Phase Four.

v. Phase Four: Decline

The market has evolved through offers from competition and the company’s products do not meet market expectations. Sales and cash flow decrease and ultimately the organization dies.

The OLC models have some relevance for mono-product businesses. Modern companies are bound to have many lifecycles as their businesses are equivalent to a succession of organizations. It is the process of bringing the sequence of several internal businesses into a long-term growth curve that is the biggest challenge. Those organizations are like wheels: a declining business can be sustained because other businesses within the large organization are in Phases One, Two and Three. Depending on the life cycle of each of these businesses, an organization develops a unique pattern which, unlike biological bodies, may envisage a long extension of life. A typical example is Corning, a thriving technology company created in 1868.

II. OLC and Schumpeter’s Waves of Innovation

Innovation waves creating new industries follow a life pattern similar to any OLC. The observation of industry stages through time shows a sensible acceleration of the process as industries are being displaced faster and faster.

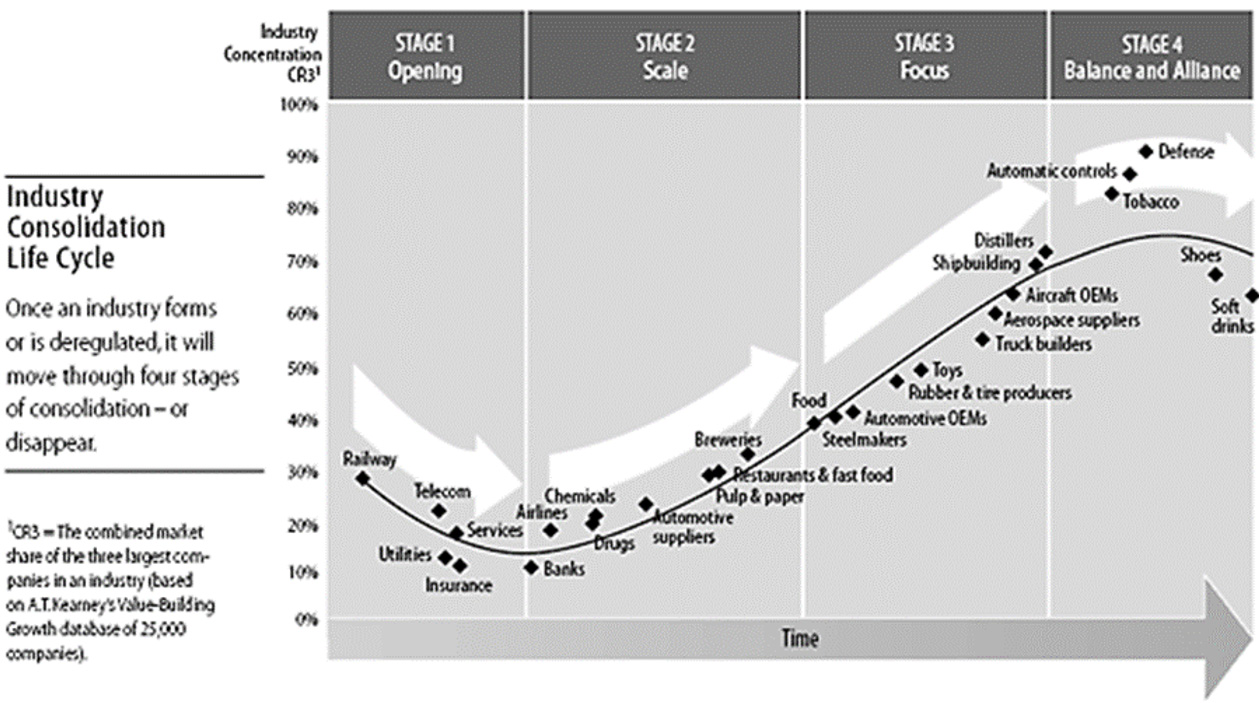

“Today, we predict, an industry will take on average 25 years to progress through all four stages; in the past it took somewhat longer, and in the future, we expect it to be even quicker. But, our research suggests, every company in every industry will go through these four stages—or disappear. Thus, an understanding of where in the cycle an industry is should be the cornerstone of a company’s long-term strategic plan.” (G.K. Deans, F. Kroeger, S. Zeisel, Harvard Business Revie, December 2002)

Source: G.K. Deans, F. Kroeger, S. Zeisel: The Consolidation Curve, in HBR December 2002

For each of the four stages described above, a specific expertise is required to thrive. In Stage 1 the focus is on creating high barriers to entry through intellectual property and a unique value proposition. The new industry is still defined by one innovator. In Stage 2 competitors have flocked into the new highly profitable industry and two or three major players own a significant share of the market. Hiring and retaining talent together with developing mergers and acquisitions skills become the key expertise. In Stage 3, industry consolidation is shrinking the number of significant players. Becoming the ultimate global industry powerhouse is the goal. It is achieved by focusing on the most profitable businesses and divesting from all other ones. Finally in Stage 4 the industry matures and the remaining power houses in these industries must create a new wave of growth by spinning off new businesses into industries in early stages of consolidation.

The advantage of this approach, much broader and more closely related to the modern real world than the simple life cycle approach, is that it links each stage to aspects of a strategy and a type of structure.

“Ultimately, a company’s long-term success depends on how well it rides up the consolidation curve.” (ibid.)

III. Successful Technology Companies Decline Like Other Businesses

Irrespective of the size and status of the business, fatal mistakes can quickly wreck any business. If death is not always the immediate issue, at best these businesses fall in oblivion. Some are acquired for pennies in the dollar (or cents in the euro) and torn apart.

a. Causes

Generally, it always comes down to the management team’s lack of vision. Complacency brought by success tends to blur the vision. Running cash cow businesses may be a blessing; it may also be a curse. Managers are too busy protecting their turf, focusing inwardly instead of outwardly. Market shifts, competitors’ innovations are either not perceived at all or under-estimated. Management then fights the wrong fight, and their value proposition loses its appeal.

I will add the easing of hiring policy as a significant cause. Businesses must maintain a discipline of regularly hiring talent to keep the pace of innovation, and of ideas challenging the status quo. Bar a proactive policy, a successful business painstakingly built in twenty years falls apart in less than two years.

Entrepreneurs and leaders of startups that are still burning cash may regard as a cause for decline the inability of raising funds in a timely fashion due to capital market conditions. It is arguable, as a good manager must always take advantage of the availability of capital and load cash as much as possible to avoid a crash, instead of fearing dilution.

b. Can time-to-decline be expanded?

Managing is foreseeing. Hence, survival implies anticipation in order to constantly extend Phase 2 of the OLC without taking an eye off the cash flow generation. Leaders must pursue three fundamental courses

• Deliver superior customer service. It must be rooted in the business DNA.

• Organize a portfolio of products/activities by bringing new products to markets in a continuous fashion. Innovation fosters growth.

• Invest extensively in talent: hiring and training are core to the business. It takes place at all levels.

Some exceptional companies have survived over a century and maintained relevance as industry leaders, such as Corning and DuPont, in the U.S., Beiersdorf, Daimler Benz and Siemens in Germany, Hitachi in Japan, the Tata Group in India among others. They never stop focusing on long-term, despite the accelerating pace of emerging technologies. As a result, their moat is more and more unassailable.

There are various ways to achieve such goal: the traditional way, the “modern way”, and the consolidator way.

i. Traditional way: Diversification

• Horizontal diversification: Targeting existing customers with additional products.

• Concentric diversification: Targeting new customers by adding products related to the existing line.

• Conglomerate: a conglomerate is a company encompassing several businesses that can be bought and sold independently as they hold no relationship between them. It is operated by a strong core corporate management team. The approach is a financial approach that emphasizes a strong control process with highly standardized dashboards for the business operators who follow a strict reporting discipline. General Electric Corp. before its breakup was the epitome of the conglomerate type.

ii. The Modern Way: The Innovation Engine

In the last thirty years, with the fast pace of new technology introductions, industry leaders started to build internal processes to foster a perpetual movement of innovation, de facto reinventing their businesses, wave after wave. John Chambers, at the helm of Cisco from 1995 to 2015, was an expert at staying ahead of the game by assembling a broad team dedicated to cranking innovations and managing obsolescence.

Managers should not be afraid of cannibalizing the existing cash cow with new businesses, provided the life expectancy and the growth of the new business yield a better outcome over time.

iii. Preying on other businesses: M&A

Mergers and acquisitions have been around for ages. Acquiring businesses (“external growth”) is deemed the fastest way to grow in terms of revenue. However, integrating an existing company with its culture, decision-making process and systems, within another company is a harder challenge than is usually recognized. Yet transactions in the technology realm have become commonplace.

IV. The Apparent Paradox of Modern Business Organizations

a. Few Startup Entrepreneurs build a lasting business

If we disregard the 75% (Europe) or 80% (US) of technology startups that fail, the entrepreneurs of the 20%-25% successful startups contemplate the options of (i) selling the business to a predator from the same industry or to a private equity fund, (ii) listing the company on an exchange, or, rarely, (iii) buying out its investors and continuing as a profitable private entity. (see our previous Blog here). The last two options, representing less than 25% of the total, and some years less than 5%, enable to maintain the independence of the business and, when the perspectives are positive, offer a chance to build a long-lasting organization.

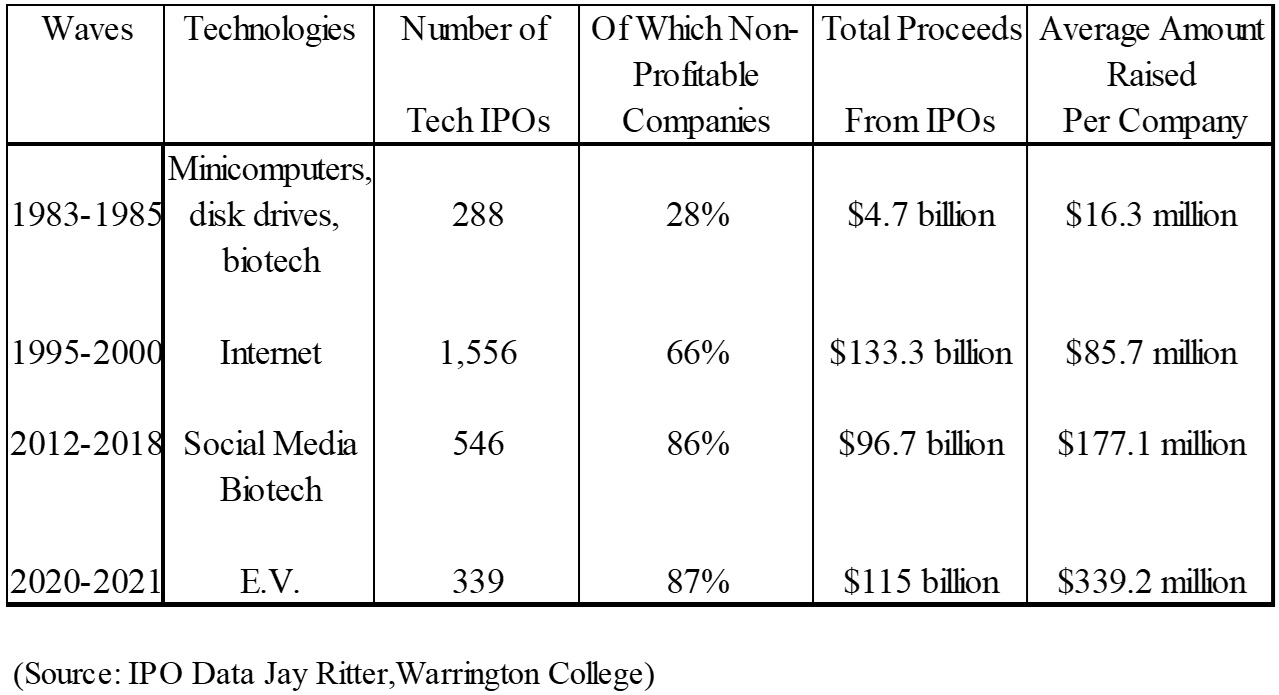

In the last half century, following the foundation of NASDAQ and its less stringent rules for listing than NYSE, non-profitable startups were able to become public. An analysis of the evolution of past IPOs of high-technology companies unveils the increasing share of non-profitable ventures accessing public funding. It is not my purpose to judge whether public investors, overfed with disclosures of all kinds, are well-suited to fund high risk businesses.

b. Evolution of Modern Time Technology IPOs

While the two most valuable companies in the world, Apple and Microsoft, were both profitable at the time of their listing (1980 and 1985 respectively) most startups that became public were not. We observe however that the biggest creation of value among the tech IPOs over a period of almost 40 years, was originated from companies that were profitable at the time of their IPO, to the spectacular exception of Amazon.

In the period 1982-83, a few tech startups raised capital through an IPO, without any history of profit. Of this cohort almost none was around in 1990. Amgen is a rare case of a surviving company that became very big. It quickly turned out to be highly profitable following its IPO. The alleged boom-bust cycle of tech stocks leaves at each wave a handful of strong survivors versus a vast carpet of moribund businesses. Among the U.S. tech IPOs from 1980 to 1999, less than 20% survive as an independent organization in 2024.

At each wave, the amount of capital raised through IPO, i.e. on top of private capital raised earlier, is of an order of magnitude higher than at the precedent wave. (Amgen raised $40 million in 1983; Akamai raised $217.6 million in 1999; Facebook -now Meta- raised 6,761 million in 2012; Rivian raised $11,930 million in 2021).

The paradox of the tech IPOs: they require more and more cash as their burn rate becomes higher, wave generation after wave generation, yet they become displaced faster as wave leaders.

c. Role of VC secondaries

For companies that cannot execute a timely IPO and that are not attracting a buyer, though they remain an ongoing business with some potential, a special investment vehicle is facilitating the exit for initial investors and founders that were locked in otherwise. This vehicle called “secondary”, provides liquidity to early investors. New investors then hold shares, replacing founding and other investors wishing to exit. It is a private transaction, sometimes difficult to execute as investors in startups are generally constrained by clauses (right of first refusal for instance) that make the transaction subject to an approval of certain classes of shareholders. As secondaries are not providing capital to the business, they have no bearing on the resurgence of growth, unless the new investors help the venture to access a new round of funding and execute upon the vision or to pivot to a new product, new market or both. Secondaries have been growing fast through the creation of specials funds, but the market for secondaries represent still a small fraction of the market for startup investors. The emergence of mega funds ($10 billion and more) gave visibility to this new form of participation into private companies. There is a risk that too many unprepared investors rush to these funds, lured by prospective high returns.

V. Is Industry Concentration Inevitable?

a. The need for bigger and bigger capital to move up the ladder of the wave.

It takes $5 billion to $10 billion to build a new fab for semiconductors, anywhere from $20 to $50 billion to bring a 5G network up in service, $5 billion to commercially launch a vaccine, $5 billion to launch an EV battery manufacturing plant, etc. Such investments can be made by large companies, though startups have managed to be successful in raising considerable amounts of money to position themselves as the early market leaders. We estimate that a new wave of industries benefits at first about twenty firms. Very quickly, in less than five years, that number is reduced to a handful, through a mix of acquisitions and bankruptcies.

b. The rise of APEX predators

The most likely leaders who will come out at the top of new industries are those who will have the resources to consolidate smaller players with their businesses. They are the future apex predators of the business world. Because of their dominant position in broad ecosystems, we could easily believe that apex predators are immune from any decline. Companies like Alphabet, Amazon, Amgen, Apple. Huawei, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia have built a big moat that makes them look like built for centuries ahead. Nothing is further away from the truth.

What would make an apex predator fail? Jeff Bezos once stated: “I predict one day Amazon will fail. Amazon will go bankrupt. If you look at large companies, their lifespans tend to be 30-plus years, not a hundred-plus years.” (2018) Yet Amazon is the only apex predator that puts customer satisfaction at the core of its mission.

At a time when all businesses rush to understand the potential of AI and how its use can provide answers to all questions, it does not take too much imagination to anticipate a new wave of companies that will unseat some giants.

Conclusion

High-tech entrepreneurs must assess where their business stands within its own lifecycle and within its industry lifecycle to optimize their products portfolio and plan its growth. They must always be prepared to assess and grab an opportunity out of their core business. By dedicating a special team to technology scouting they are prepared to execute a perpetual innovation strategy. Such strategy coupled with a tailored capital strategy is the preliminary step to reach the Holy Grail of enterprises.

One should not be positioning its venture to fit in a box to address the appetite of one particular predator but seek to distinguish its business to ride a new wave and maintain relevance in the long term.

“Instead of being really good at doing some particular thing, companies must be really good at learning how to do new things.” (Martin Reeves and Mike Deimler, in HBR July-August 2011)