SPECIAL PURPOSE ACQUISITION COMPANIES (SPAC)

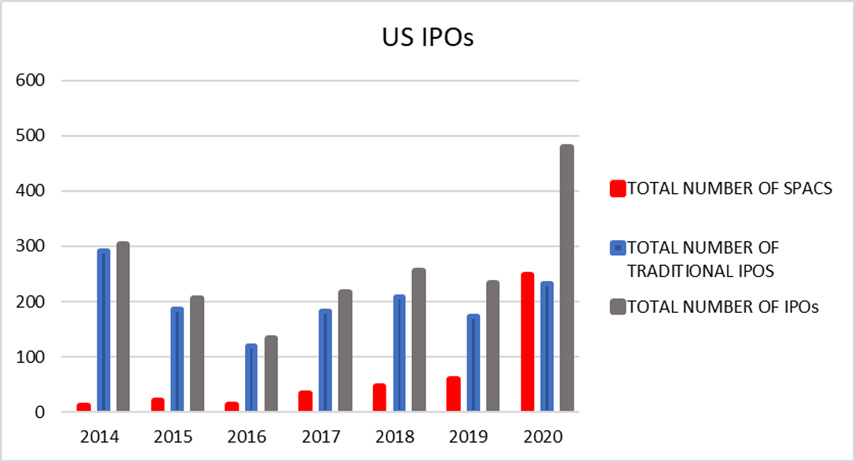

Sources: Stock Analysis, Spac Research.

What are SPACs? Why did they become so popular? how do they work? Do they provide the best path for high-tech companies to become public?

What a SPAC is

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a company with no commercial operations, that is formed strictly to raise capital through an initial public offering (IPO) for the purpose of acquiring an existing company, generally privately held. SPACs are also dubbed “blank check companies." Following a business acquisition, the SPAC will continue the operations of the acquired company as a public company, under the name of the acquired company, just as a reverse merger transaction.

For entrepreneurs and major private investors in a technology company, it represents an alternative to the traditional IPO, with the same achievement, i.e., listing the company on a stock exchange, and making its stock tradable and liquid.

How It Works

A SPAC is generally formed by a group of investors, “the sponsors”, with a recognized background in a particular industry or business sector. Most SPACs limit themselves to particular industries, but the selection of the target company to acquire is a subsequent event. Founders/Sponsors invest nominal capital in exchange for preferred shares or “founder shares” and raise funds through an IPO as a blank check company. A SPAC also may increase its capital by selling securities in private offerings, resulting in negotiated terms for those securities that may differ from the shares sold in the IPO. These funds will be dedicated to acquiring a business. A variant of the acquisition of an operating company by a SPAC is a reverse merger when a privately held operating company acquires an existing publicly held SPAC, therefore becoming public.

Once the SPAC has identified an initial business combination opportunity, its management negotiates with the operating company and, if approved by SPAC shareholders (if a shareholder vote is required), executes the business combination. This transaction is often structured as a reverse merger. The combined company, following the transaction, is a publicly traded company and carries on the target operating company’s business.

SPAC IPO proceeds, net of certain fees and expenses, are held in a trust account. SPACs generally invest the proceeds in low risk, interest-bearing instruments. these interests are the only income the SPAC receives.

On IPO, founders are generally issued a combination of ordinary shares, founder shares and warrants, which carry a one-year locking period for the bearers. Investors are remunerated with shares and warrants giving them the right to acquire additional shares at a 15% premium to the IPO price in the vehicle. The sponsors shareholding at the end of the transaction reach on average 15% to 20% of the outstanding shares. This often includes preference shares entitling them to a certain proportion (often 20%) of the upside when the share price of the company, following its acquisition. reaches a certain threshold, generally 15% above the IPO price.

The founder shares ultimately convert into ordinary shares after a defined period following completion of the acquisition.

The introduction of the SPAC to potential investors is like regular IPOs, involving a roadshow where information is presented. Information here refers essentially to the background of the sponsors, the target industry, if any, and the adequation between the sponsors ‘background and the target industry. Early investors are basically relying on the sponsors' reputation in the hope of participating early on in a promising investment.

The terms of the SPAC specify a given time frame, a maximum of two years, in which a merger must be completed. If that time expires without an acquisition, then the SPAC will return the raised capital to the investors through a liquidation process.

The most important benefit of a SPAC is that the IPO process is a lot simpler than it would be for an operating business. A reverse merger with a SPAC allows to avoid any registration filing with the regulator.

When a SPAC issues securities to its sponsors, the terms of those securities often differ from securities it issues to public shareholders, giving the sponsors substantial control over the SPAC.

Once the SPAC has identified an initial business combination opportunity, the shareholders of the SPAC vote on the initial business combination transaction. Following this vote any SPAC shareholder, disagreeing on the resulting business combination, has the right to redeem its shares and receive its pro rata amount of the funds held in the trust account. If the deal goes through, the investor funds in escrow are then used to purchase the private company.

For private companies, SPACs offer a shortcut for going public, without the extensive public scrutiny and investor roadshows typically required in the traditional IPO process. Here is an example of a Public SPAC object (from the website of Social Capital Hedosophia): “IPOE may pursue an initial business combination target in any industry or geographic location (subject to certain limitations). IPOE intends to focus its search for a target business operating in the technology industries. NYSE Listed: IPOE.U (units comprised of shares and warrants)”. It would be difficult to make a vaguer statement for an investment company! It operates as a bait for technology entrepreneurs from anywhere in the world who wish to list their venture on a public market and trust the sponsors at Social Capital Hedosophia -those who acquired 49% of Virgin Galactic in 2019- are best suited to lift the status of their business.

History

SPACs have been around for decades. In the 1980s, blank check companies used to offer thinly traded penny stocks or "pink sheets." The promises of a sharp appreciation of unknown companies never materialized. Hence the reputation of blank check companies was associated with quasi fraudulent businesses.

Since the late 1990s however, the SEC tightened regulation of SPACs, as they came to be named, has promoted SPACS to a more legitimate status and institutional investors started to show interest. Such regulation involves the conservation of investors’ money in a trust or escrow account until the target company is publicly disclosed, and the obligation to register with the SEC. SPACs grew popular again until the financial crisis, when IPOs in general and SPAc in particular were practically halted. From 2015, a few SPACS reappeared.

More recently, an excess of available capital has led investors, mainly private equity funds, to broaden the net for merger and acquisition opportunities, triggering the return of SPACs. Private equity funds have become key users of SPACs. The Gores Group, for example, has created so far eight SPACS. Gores was a pioneer among private equity funds to consider SPACS as both a path to liquidity and an alternative way to acquire companies. The first Gores Holdings SPAC consummated its reverse merger in 2016.

Big-name entrepreneurs, hedge-fund managers, investment banks and celebrities like Richard Branson, Michael Jordan and Shaqille O’Neal became involved in SPACs.

SPACs tend to acquire growth companies — start-ups and fledgling firms — which, by their nature, are higher-risk than, say, established blue-chip companies. SPACs have been a fast-growing financing path for clean-tech and transportation companies, including high-profile electric vehicle ventures, such as Nikola, in 2020. 26 companies in the transportation sector merged or began the process of merging with a blank-check company, representing a combined valuation of over $100 billion. This is a potential bonus for early stage startups as the listing of so many venture backed companies frees capital that VCs may dedicate partly to newstartups, reversing the trend of the last few years.

SPACs are, after all, just a financing scheme, an alternate route for companies to go public that requires fewer disclosures than a traditional IPO or direct listing process. In exchange for this easier process, the company being taken public offers a bigger part of itself for sale to the SPAC sponsor.

Track Record

According to Renaissance Capital, of the 313 SPACs IPOs since the start of 2015 to the end of the third quarter of 2020, 93 have completed mergers and taken a company public. Of these, the common shares have delivered an average loss of -9.6% and a median return of -29.1%, compared to the average aftermarket return of 47.1% for traditional IPOs since 2015. Only 29 of the SPACS in this group (31.1%) had positive returns. It is obviously not favorable to SPACs, considering that the period was that of an unprecedented bull market.

The optimists always refer to the bright side of the industry, not the least the performance of Virgin Galactic Holdings that has appreciated 146% in the year since it went public via a SPAC in October 2019.

Why do they Exist

There are two main reasons why SPACs have been so hot:

- Retail individual investors have longed to get access early on to the IPOs of highly visible technology companies, at the same level than professional investors. This is an opportunity for them to participate on the ground floor of an IPO, prior to the first-day price surge.

- High-tech startup entrepreneurs, investors and management find a fast track to a listing without most of the paperwork of a traditional IPO. A traditional IPO consumes about 6 to 8 months of management time, whereas in the SPAC alternative, in three months a listing can be achieved.

Differences from a Regular IPO: the Reverse Merger IPO

Many entrepreneurs, early investors and management in private technology companies perceive a reverse merger with a post-IPO SPAC as a cheaper, faster alternative to an IPO, with more price certainty and providing a higher valuation for their business.

There have been talks since 2019 of the “broken” IPO process. The traditional IPO underwriters and managers have often underpriced companies going public, as IPO prices could skyrocket on Day One of the listing, as did Snowflake priced at $120 opened at $245 on its first trading day. Company founders, employees, and investors perceive this apparent exuberance as a steal. I view this more as an incentive for entrepreneurs and their team as an incentive to keep their shares a little longer. In 2020, the average company going public was underpriced by 31%. Do SPACS provide a better option?

Unlike an operating company that becomes public through a traditional IPO, a SPAC is a shell company when it becomes public. It does not have an underlying operating business and does not have assets other than cash and limited investments, including the proceeds from the IPO.

IPO Investors in SPACs are relying on the management team that formed the SPAC ( the sponsors), as the SPAC looks to acquire or combine with an operating company. In the IPO, SPACs are almost always priced at $10 per unit. This price is not based on a valuation of an existing business. When the units, common stock and warrants (more below) begin trading, their prices fluctuate, with no fundamental reason other than some investors may value some sponsors more than others.

Compared to a traditional IPO, a SPAC saves time and money, as the level of disclosure is much lighter.

SPAC IPOs are executed rapidly because only the sponsor and the target company negotiate around the table while a traditional IPO involves investors, issuers and underwriters negotiating several terms.

A traditional IPO or a direct listing will take an average of 6-8 months to begin trading, while a SPAC will take around 2-3 months.

The benefits of SPACs :

- Full transparency when the target is selected. SPACs must file a document with the SEC when announcing the name of the target combination company. This document is similar to the prospectus that an IPO must file (called S-1).

- Sponsors with expertise. Sponsors with a track record at acquiring company with unlocked value give a high credibility to the SPAC. Private equity specialists play this card against competing SPACs lacking that sponsor’s experience.

- An easy exit. Investors unhappy with the target acquisition can opt out by selling their shares before the acquisition is finalized.

Traditional IPOs still happen. Tthey are expensive and time-intensive, and the bar and expectations for a successful listing has changed in the last ten years. Today the money raised in IPOs is often above $500 million on a multi-billion value. For instance, in September 2020, Snowflake raised $3.4 billion and its value at the end of the firs trading day was $70 billion.

While SPACs access the public markets to raise capital to fund a future takeover, PIPEs are the vehicle of choice to raise additional moneys for the combined public companies. PIPEs, or private investments in public equity, are investment vehicles to raise capital privately from a select group of investors. These investors are given material, non-public information from the SPAC about the target they’re looking to acquire. They are often granted a discount to the SPAC’s IPO price About one-third of SPACs in the 2019 through 2020 merger cohort that issued shares in PIPEs, sold those shares at a 10 percent discount or more to the IPO price. As PIPEs are increasingly being used in SPAC mergers, a broader group of investors attempt to participate. Yet it has remained a select circle that is invited to invest in PIPEs. In 2020, PIPE capital raised on 46 business combinations exceeded $12 billion.

Existing shareholders, essentially the operating company initial investors and management are diluted. So are the investors that blindly invested in the SPAC IPO without access to the disclosures given to the PIPE investors.

A new competition to SPACs is appearing that will be of interest to many technology companies. Since December 2020, a direct listing on the New York Stock Exchange allows companies to raise money. This was not the case when Spotify chose the direct listing to become a public company in 2019, allowing its shareholders to trade their shares, but receiving no fresh capital to fuel its growth.

What Kind of Disclosures are Necessary in a SPAC IPO?

Disclosure in a SPAC IPO prospectus is limited to the SPAC’s acquisition strategy and criteria, its capital structure, the biographies of its directors and officers, and the terms of the underwriting arrangements. There is no historical financial information available and the risk factors are limited and boiler plate, especially as no definite acquisition target is known yet.

Consequently, the due diligence investors can make is limited compared to the high level of due diligence expected in a traditional IPO where disclosures in the prospectus are lengthy.

Disclosures about potential conflicts of interest between the sponsors and the principals of the SPAC, on one hand, and the interests of public shareholders, on the other hand, when recommending a business combination transaction, must be clearly stated. “Unlike the traditional IPO process where a private operating company sells its securities in a manner in which the company and its offered securities are valued through market-based price discovery, these individuals are solely responsible for deciding how to value the private operating company and how much the SPAC will pay for it.” (Source: SEC)

In addition, SPAC sponsors, directors and officers may have fiduciary or contractual obligations to other entities than the SPAC. Such obligations must be disclosed to investors, as conflicts of interest may arise between one or more such entities and a proposed combination business target.

Other important disclosures Sponsors need to provide relate to:

- the favorable terms at which they acquired SPAC securities compared to investors in the IPO or subsequent investors on the open market. Sponsors will benefit more than investors from the SPAC’s completion of an initial business combination and may have an incentive to complete a transaction on terms that may be less favorable to investors.

- The amount of control after the business combination is complete

- Potential interest in the private offering that follows the IPO, and its terms compared to the IPO terms.

- Any potential personal benefit taken from the business combination selected.

A SPAC is a fast-track public offering for operating companies. The paperwork is considerably reduced compared to a traditional IPO. However, a SPAC is only as good as its sponsors: this matters as much to the principals of the operating company to be reversely merged as to investors in the SPAC.

SPACS Grow Also in Europe

SPACS have been around in the UK and in continental Europe for more than a decade. The first SPAC listed on the Euronext Amsterdam exchange, raised approximately €115 million in July 2007, followed by another SPAC, raising €600 million in January 2008. In the UK, the first SPAC raised funds in 2003. Others have followed in both regions. Unlike in the US, after the financial crisis, investors were seeking investment opportunities that had become unavailable and SPACS surged in the UK from 2009 to 2011. However, following a series of high-profile failures, SPACS quickly became out of fashion, until 2016 when they resurfaced.

The SPAC purpose and process are similar in the US and across the Atlantic. Two significant differences in the UK, however, must be indicated:

- In the UK, after completion of the combination, the listing of the resulting shares of the enlarged SPAC is cancelled. To remain public, a prospectus needs to be published for readmission to trading. This makes the attraction of the SPAC less tangible than in the US, as management will spend time and money as in a traditional IPO.

- No shareholder’s approval is required in the UK SPACs to proceed with an acquisition (except for the AIM listed SPACs). This makes the fundraising harder as investors in the UK cannot opt for an exit from the deal and get their money back as in the US

Since 2019, the number of European SPACSs grew significantly, though not as much as in the US. Most of them, however, raised funding in the US, seeking a listing on the most liquid public market, targeting European businesses with global ambitions.

Still, German SPACs that targeted cleantech companies have successfully invested in companies that resulted in listings on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. As in the UK, there is confidence, among professional bankers involved in the space that the SPAC market will develop and mature. I am personally more circumspect as I view the success of SPACS as an indirect result of the excess capital available, which is directly induced by central bank policies. If and when inflation rises above the accepted limit rate, central banks will tighten their monetary policies. Then, only the very best sponsors, as well as the very best operating target companies will not be affected.

Risks for entrepreneurs

Entreprises are “picked” by sponsors of SPACS who, by definition, are masters at deal making. It is not certain that a good technology company would not find a better price through a regular IPO if the underwriters are well attuned to the market. “leaving money on the table” is supposed to be the great argument in favor of SPACS vs. conventional IPOS. It is not proven by track records. The deal is generally great for sponsors, could be good for investors, and is acceptable for enterprises only if these enterprises cannot find a regular access to IPO because it does not fulfill the more stringent requirements. It seems Richard Branson made the same assessment, witnessed by his moves: this outstanding entrepreneur realized there was more money to be made as a sponsor than as an entrepreneur.

It is critical that entrepreneurs evaluate the background and track record of the management of the SPAC. Having been in the limelight for years is not a guarantee of quality, ethics, and investment savvy. Some management teams have a great track record of finding companies that continue to increase in value over time, while some just have a knack for closing the deal but the companies they choose tend to disappoint. Others barely get the capital to close the deal and the stock craters on the first official trading day.

Conclusion

SPACs are, after all, just a financing scheme, an alternate route for companies to go public that requires fewer disclosures than a traditional IPO or direct listing process. In exchange for this easier process, the company being taken public offers a bigger part of itself for sale to the SPAC sponsor.

Traditionally, this higher level of dilution made SPACs attractive for turnaround stories. Existing shareholders in a business that is struggling are typically more willing to give up an ownership stake in exchange for fresh capital, or a new management team running the company.

High growth companies are now, however, targeted by SPACS, while the stock markets are in euphoria. Entrepreneurs and CEOs leading outstanding technology companies with high growth and good profitability may think twice before choosing the route of the SPAC vs. a traditional IPO. The instant valuation may be a factor in the craze for SPACs. It is not proven, though, that entrepreneurs would not leave on the table a greater amount due to dilution than what they would give the public investors through what is deemed mispricing. What matters is whether, down the road, the value of the business keeps growing, and acquisition opportunities can be easily funded by secondary offerings at a much higher price than the IPO’s.

It looks like SPACs are attractive for entrepreneurs ready to throw the towel and take the money while it is available. Burnt out entrepreneurs may find it is a decent, worthwhile exit, even if they stagger it in two years. A good sponsor would not be necessarily lured to acquire such business.