ALL IPOS ARE NOT EQUAL

An IPO is not an Exit for founders. It is an opportunity to broaden the potential of the business. Investors, mainly venture capital investors, have used the term Exit for themselves, and it should remain restricted to them.

1. Why is an IPO the Holy Grail?

a. It grants credentials that are valuable in commercial relations. Suppliers and customers are comforted when they deal with a publicly listed company.

b. Recruiting talent is facilitated. Hires are attracted by a stock-option program that converts into tradable shares within a real market.

c. It makes it easier to acquire businesses with a currency that is priced every day: external growth can be generated quicker.

d. It renders all shares (after the lock-up period) liquid.

e. Secondary offerings can quickly be launched when necessary. Funding subsequent growth steps becomes stress-free.

2. A Public Listing Does Not Suit All Entreprises and their Leaders

It is harder to run a publicly listed company than a private company:

a. Public companies face intense scrutiny from market authorities, regulatory agencies, and the public.

b. They are obliged to provide required disclosure on the business and the strategy, some of which informs competitors.

c. The multiplicity of recurrent report filings is an expensive and time-consuming process that legitimates a full team around the CFO dedicated to keep the company compliant with all regulations.

d. Unless the structure of votes provides for a stable majority, a public company is more exposed to potential hostile takeovers. However, there are available remedies (so-called anti-takeover pills).

3. Many Businesses Fail as Public Companies. Why?

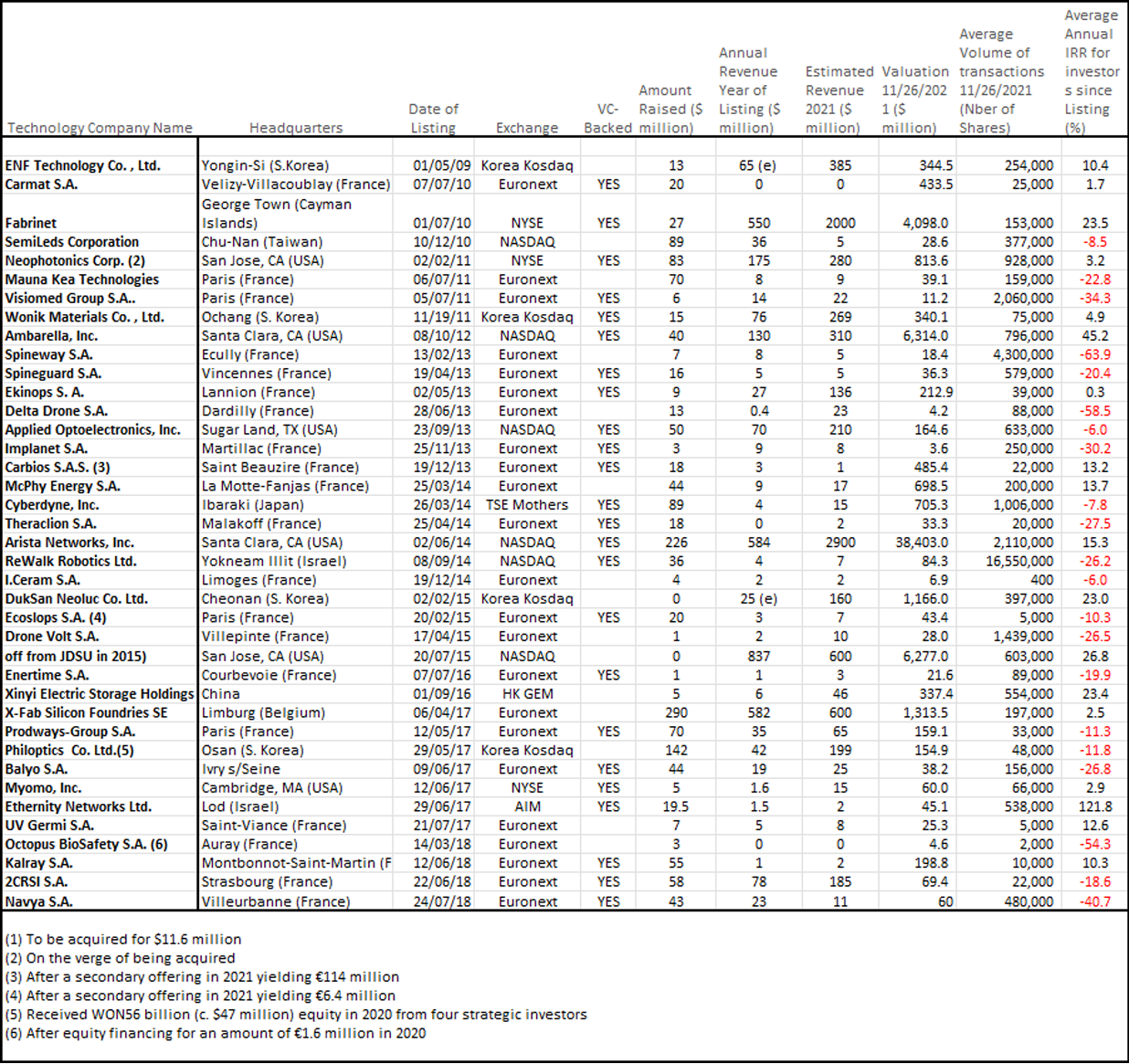

Since the early 1980s, technology IPOs have followed extreme highs and lows, once becoming the rage before being abandoned, then another cycle starts with another wave of new technologies, reproducing the same pattern. Profitable companies survive, some reaching unbelievably high values while the rest dwindle and perish. The present cycle, that followed the financial crisis of 2008 is witnessing a high number of IPOs. Not all have been successfully led. Below is a table on companies from industries of interest to J&M Lab, essentially deeptech, medical equipment and environmental technologies, who obtained a public listing between 1/1/2009 and 12/31/2018 on the biggest stock exchanges. Though there were many more IPOs in the last three years than in the period from 2009 to 2018, taking the sample under review allows to observe how companies have fared, at least three years after their IPO. The selected companies had a maximum of 20 year of operating history at the date of their first listing and were not acquired until November 2021.

As expected, such companies represent less than 5% of all IPOs, except in Korea. It excludes companies that went under and companies that were delisted by the Exchange for lack of minimum compliance with the public-listing rules set by the respective exchanges. This is not an exhaustive list. It is however quite representative.

This table shows:

- 25 out of 39 companies were previously backed by venture capital. This is not a surprise. Venture capital investors are familiar with the listing process, provide valuable contacts at investment banks and generally capture the right timing when the stock market appetite for IPOs is favorable.

- 21 out of 39 companies have had a negative internal rate of return for investors investing at the IPO or at their direct listing (Lumentum did not raise money when listing).

- Six had a return rate higher than NASDAQ for the same period (18.7% in average): two companies listed on NASDAQ, one on NYSE, one on London AIM, one on Korea Kosdaq and one on Hong-Kong GEM.

- 9 have been trading with a low volume (under 50,000 shares a day in average)

- 8 have not shown any revenue growth since their IPO.

This is not a stellar outcome by any standard. One can find the origin of this result in three causes:

a. Entrepreneurs’ illusions. Most entrepreneurs have a tendency to overestimate future accomplishments. Their revenue and profit forecasts are attractive. They do not lie, as they believe in the forecasts. Great entrepreneurs differ as they provide a set of data they have validated.

It is the duty of investment bankers to harass CEOs and CFOs with hard questions. Only when all the responses meet with their approval should an IPO proceed. In other words, some completed IPOs could have been avoided, or postponed. A lack of high-quality due diligence results in loss of reputation for the investment bank and the entrepreneur, and a capital loss for investors.

b. Stock-exchange illusions: because of the growing competition between exchanges to attract startups, the rules each stock exchange sets to become more alluring create their own demise. Under the pretense of offering retail investors the “opportunity” (sic) to invest early in the future Apple or Facebook, they squander shares of companies that have yet to prove how their business model leads to profitability, and sometimes even whether their products are validated by the market. Some markets accept to list companies after only two years of operating history with no revenue.

c. investors’ illusions. Retail investors want to believe more in a new investment than to find reasons not to invest. There is an aura attached to IPOs of high technology companies. Stories of Apple and Amazon IPO successes for early retail investors are enough to instill hope that the investment in play will deliver another of those exceptional capital gains. Credulity is a good friend of greed.

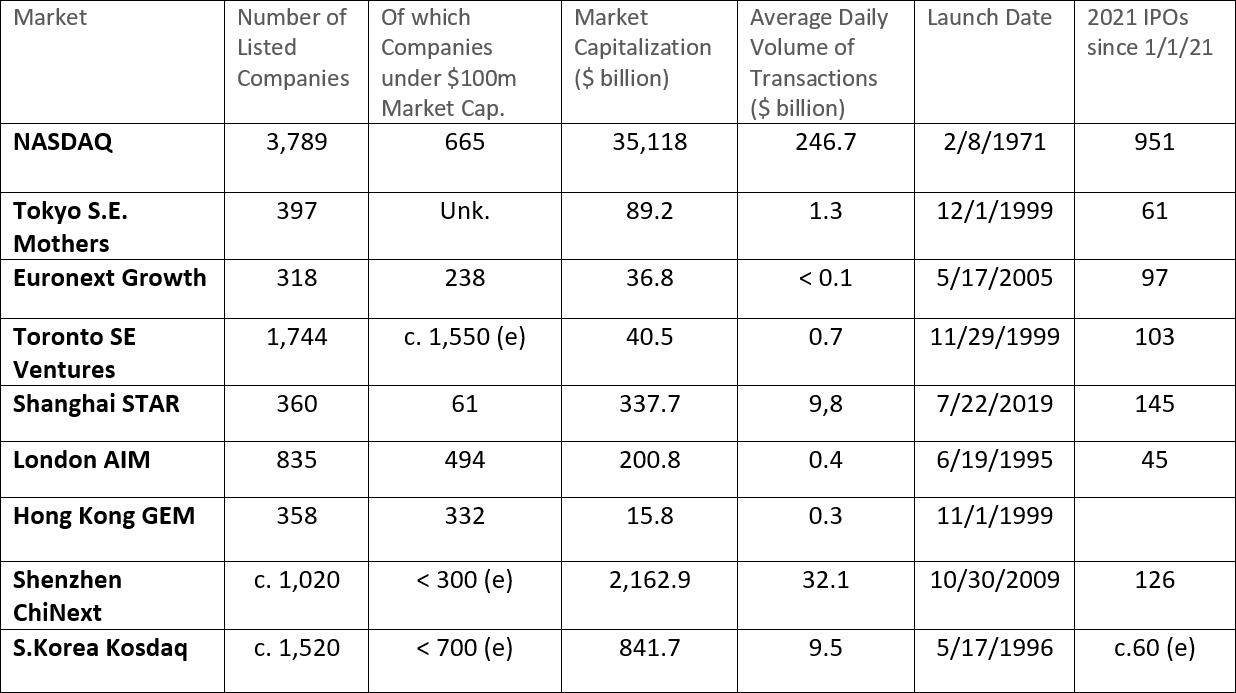

4. NASDAQ and Its Aspiring Clones

NASDAQ has been operating for fifty years, starting in1971 as the first world electronic trading market. Twenty years later 46% of all US public equities were listed on NASDAQ. It has become the market of choice for most high technology IPOs, while the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), requiring three years of profitability to qualify for a listing, shut itself from most of this massive new opportunity. Such a success did not go unnoticed and areas with a significant cluster of innovative companies and a progressive private capital market attempted to emulate their US model. Five new markets sprang up during the dotcom boom (1995-1999), all of which as an initiative within a larger stock market (Tokyo, London, Hong Kong, Toronto, South Korea). Below is a table summarizing the main data for the biggest of these stock markets for young companies. It appears the expected results were not achieved, to the exception of Shanghai STAR market, for which records span too short a period. Unlike NASDAQ, most of these markets were initiated as a step towards a “mature listing”, allowing companies that reached a certain size to “graduate” to a higher-grade listing. This system of a de facto springboard did not prove effective. The growth of these junior markets has been hampered by many delisting and bankruptcies among newly minted companies trading on their platforms. Some went the way of oblivion, lacking the promised growth, the majority did not deliver the anticipated numbers beyond one or two quarters following the IPO. Yet these markets assumed they had applied the lessons from the book as written by NASDAQ: they were all created to accept new listings with less stringent conditions than their elder respective exchanges. Unfortunately, none of them is an independent company with a creative mind of its own. Today the EU is toying with the idea of a new European equity market. It would mirror the Chinese markets, as today the Chinese authorities founded the Beijing Stock Exchange to complement the Shenzhen and Shanghai markets all under the same authority (Hong-Kong being legally independent from it). A private initiative, gathering, for instance, all market makers of the area under a professional leadership with a mission that does not resemble a political mission, may have more chances of success.

Hong-Kong and Shanghai are the biggest markets after NASDAQ and NYSE. Because of speculative excesses that saw prices on IPO days catapulted many times over, for lack of stop system, these markets acquired a reputation for being irrational as demands for new stocks was extremely high, due diligence on smaller issuers not at par with Japanese and Korean counterparts, and financial audits leaving room for improvement. All this was progressively remedied after the great recession. One of the reasons was to stop the drain of Chinese companies IPO to the US. The other, obviously, was to protect retail investors.

Both Hong-Kong GEM and Shenzhen ChiNext have lost their luster since 2018. Almost all IPOs in Hong-Kong have occurred on the main market since then. A new listing regime was instituted that enabled pre-revenue biotech firms and innovative companies with weighted voting rights to seek a listing on the main market. I deem it a positive step. ChiNext specializes in profitable companies operating in the “new economy sectors”. The very low threshold required from investors on ChiNext had a negative influence on the quality of companies seeking a listing. The quality companies prefer Shanghai and Hong Kong. The ongoing reforms will level the playing field, it seems. It remains to be seen whether Beijing will attract part of this segment, as is the purpose of its foundation. Considering its location, it is very likely.

The Shanghai STAR Market, not even three years old, has been successful at luring ‘hard’ technology companies in high-end equipment, biotechnology & health care, information technology, new materials, renewable energy, energy saving and environmental protection sectors. It accepts unprofitable companies. It requires a high threshold for investors asset level. This is an interesting initiative for a public listing: promising startups with high-risk on one hand and wealthy public investors that mirror private placement investors in the US on the other end.

China is hoping to develop a culture of investments. Whether they will achieve to create an investment savvy community is difficult to assess. Today there are more than 100 million accounts from individual investors in the main exchanges of China. This does not mean that investment has become part of society to prepare for a later retirement. At the least down cycle, a good part of these accounts will close, and the numbers of durable investors will be much lower. Still, the efforts to encourage investment in the industries of the future are serious.

Today and certainly more tomorrow, startup entrepreneurs will have multiple options to list their company. IPOs are marketed by exchanges as a product, under intense worldwide competition. Any company that meets the requirements of a stock exchange can launch an IPO there. Apart from a listing in the US, where the volume of transactions is unparalleled, it remains a challenge: hiring a local legal team and a professional translator to list a company on the opposite region of the globe does not make a successful IPO. Caution must be exercised. Investors always question why a company from country A that has a thriving stock-market, would have its IPO on country B? And they should.

In parallel with the stock exchange reforms in China, the Tokyo Stock Exchange is restructuring its current stock market into three new market segments: Prime Market, Standard Market, and Growth Market.,

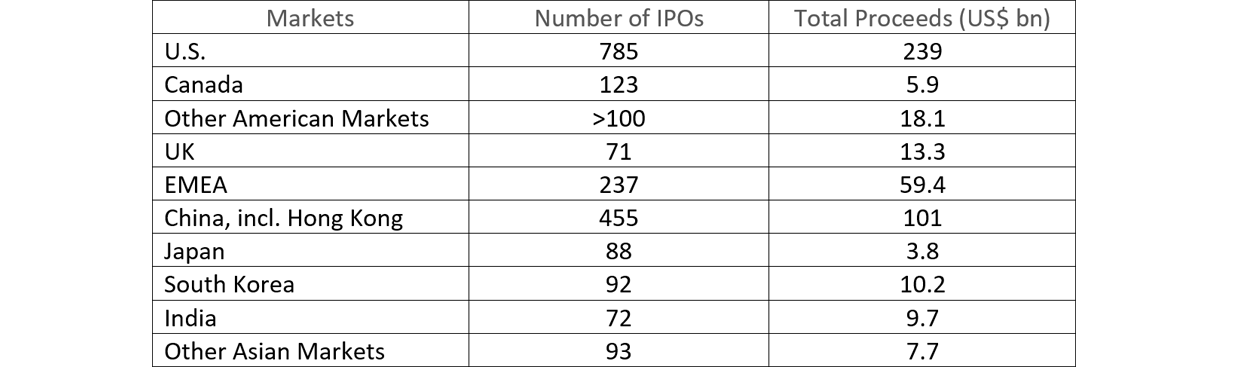

Below is the record of IPOs in volume and value by region, all sectors included, for the first nine months of 2021. Less than 40% of world IPOs are from high-technology companies, of which approximately 85% are from IT and life science companies.

A new trend is being spotted: some startups opt for multiple listings. BeiGene, for instance, is ready for an IPO on Shanghai’s STAR Exchange. The company completed an $182 million IPO on NASDAQ in 2016 and a $900 million IPO in Hong-Kong S.E. in 2018.

5. What are the Fundamental Elements That Warrant a Good Market for IPOs?

a. Liquidity: you need liquidity in abundance. If you raise less than $10 million and offer to float less than 20% of the company, you are at risk of being neglected by savvy investors and being the target of retail investors that are very volatile. The volume of transactions on your shares must be sustained so that you are able to eventually issue additional shares in a secondary offering to finance a new growth phase. It is also indicative of a healthy secondary market when needed.

b. Educated investors: this is the trickiest, as investors do not become educated overnight, or by being hit once. It is troubling to watch investors repeating the same mistakes. Many trades on the stock market, essentially from the retail side, come from apprentice speculators who confuse themselves with investors. They are the ones who create spectacular swings, up and down, making apparent that they are not becoming a company shareholder for the sake of solid fundamentals.

c. Strictly enforced rules on disclosures. Without such rules, the type of investors interested in a stock are the ones who would move to a new fad stock in a blink of an eye.

d. International accounting and financial standards; auditing rules must be clear. There are still today public firms that are not audited according to accepted standards. How can one invest in a company whose balance sheet one cannot trust?

e. Reliable licensed professional intermediaries in the ecosystem.

f. A strong financial market supervisor.

g. Reasonable daily circuit breakers for stock prices, except on the IPO day.

6. How to Prepare for a Successful IPO

Below are basic rules CEOs of companies seeking to launch an IPO are wise to follow

a. Do not rush an IPO under the pretense that on paper your venture qualifies. Nothing shines more than a good historic growth record and a demonstrated path to profitability with improving hard numbers, even if your business is not profitable yet. A rushed IPO raises a red flag.

b. If a company files for an IPO, it is imperative that it tries to raise an amount of funding that would allow to reach a recurrent cash flow positive without any recourse to additional funding. For example, Duolingo, on 7/28/2021 raised $521 million while it could already show a thin cash flow and was recording 40% annual revenue growth with improved margins. The present breed of IPOs is unlike those during the dotcom boom (and subsequent bust) of 1997-2000, when hundreds of companies, mainly based in the US, raised what was deemed a good amount of funding, though they underestimated the slowing growth coming ahead that resulted in stretching the time to reach cash flow positive to a point when they had to cease activity for lack of resources, and potential acquirers’ cold feet.

c. Have ready a good implementation plan for the two years following the IPO. Make sure you can align deliverables with more than 80% chances of accomplishment. Never bet with investors. As always, do not overpromise.

d. Selling shares to investors is like selling a product to customers. Therefore, you thrive to have repeat investors who will participate in secondary offerings, so useful in fast-growing high-technology companies.

IPOs of technology companies have flourished in the last three years, allowing to free venture capital for funding the new generation of startups, about $1 trillion in the US alone ($199 billion in 2019, $289 billion in 2020 and $513 billion for the first nine months of 2021). IPOs must be prepared far in advance only by companies that qualify completely. It is not a game for business owners who excel at dressing their business to look the part when they perceive the growth period is ending or the margins start to go down instead of up, with no reversing on sight. Accidental IPOs occur here and there in all markets. These IPOs should never happen if all investment bankers were ethical. They must make a thorough due diligence that flashes the challenges the IPO candidate is facing, and should turn it down as a client in case no good response is given.

IPOs of deeptech startups have been rare in the past decade. We trust that, with the new impetus driven by specialized investment funds in all continents, the new decade will see an increasing number of successful hard technology companies reaching the stage for a listing. As painful as the path may look, it is well worth seeking such stage.